This wonderful Romanian fairy tale plays all kinds of deliberate tricks with sexuality and gender stereotypes. It was collected (and perhaps enhanced, who knows?) by the Romanian folkorist Petre Ispirescu and was rendered into French by Jules Brun in 'Sept Contes Roumaines' (1892) with a commentary by folklorist Leo Bachelin.

The title varies from translation to translation. Jules Brun calls the tale ‘Jouvencelle, Jouvenceau' or ‘Young Woman, Young Man’ - which sounds neater in French than it does in English. Translating Brun’s story for ‘The Violet Fairy Book’, Andrew Lang’s wife Leonora Blanche Alleyne renamed it ‘The Girl Who Pretended to be a Boy’ (and added a few passages to emphasise the heroine's femininity). A translation directly from Romanian by Julia Collier Harris and Rea Ipcar in "The Foundling Prince and Other Tales" (Houghton Mifflin 1917), gives the title as ‘The Princess Who Would BeA Prince: or Iliane of the Golden Tresses’. All of these titles sound a little cumbersome in English, so I've gone out on a limb and called it 'The Princess in Armour', but kept the subtitle which refers to the second heroine of the story - for there are two!

The first heroine is an unnamed warrior princess who quite literally becomes the Romanian sun-hero, Fet-Frumos (Beautiful Son: Făt-Frumos in Romanian) - a warrior of immense chivalry and prowess. Besides his mythic origins, Fet-Frumos is the Prince Charming of Romanian fairy stories and the lover of Ileana Simziana: Iliane of the Golden Hair. Leo Bachelin considers Iliane to be the personification of youth and springtime, dawn and twilight; while he describes the warrior-girl heroine of this story as a sort of androgynous Apollo whose powers of light are bound to put shadows to flight. After all, her/his horse is called Sunray...

In the original Romanian, the heroic princess has to fight a folkloric creature called a Știmă. (Two of them, in fact.) All the translations I've mentioned above render this word as 'genie', so I've followed them - but it almost certainly gives the wrong impression, especially if Disney's Aladdin comes to mind, since a Știmă seems to be a kind of dangerous nature spirit, who often has a connection with water: this may explain why the one which holds Iliane prisoner lives in 'the swamps of the sea.' The version below is my translation from Brun's 'Sept Contes Roumaines'. The subtitle 'Iliane of the Golden Tresses' is important because Iliane is another significant personage in Romanian folk tales and mythology. According tothis article in The Journal of Romanian Linguistics and Culture she is "the heroine of numerous songs, carols, and fairy tales; the most beautiful of all fairies, their queen, so beautiful that ‘one could look at the sun but not at her’. Her epithets are ‘the beautiful’, the moon fairy, ‘lady of the flowers’, protector of the wild animals and the forests..." Given all this, the final twist at the end of the story might be taken any number of ways, but to my mind it is a consciously ironic comment on the power of masculinity.

There was once an emperor – oh yes, there was; if he hadn’t existed, how could I tell you about him? Very well then, there was once an All-Powerful Emperor. Victory after victory, he extended his empire over the whole wide earth, as far as to the place where the devil suckles his children! And he forced each of the emperors whom he subjugated to send him one of their sons to serve him for ten years.

Now, on the very edge of the borders of his realm, one last emperor stood against him. Year afteryear this emperor defended his realm and people until, growing old at last and losing his strength, he realised he too would have to submit.

But how was he going to to obey the command of the All-Powerful Emperor and send a son to serve him? He had no sons, only three daughters. How he worried! If he couldn't send a son, the Emperor would think him a rebel! He didn’t talk about it, but he imagined himself and his daughters thrown out of their lands and dying in misery and distress.

The sadness shadowing his face threw black sorrow on the white souls of his three daughters. Not knowing the cause, they tried their best to brighten up their old father, but nothing worked. So the eldest took her courage in both hands. “What troubles you, father? Is it something we’ve done? Have your subjects turned against you? Please tell us what is poisoning your old age. To blot out the least of your troubles we would shed our blood. You’re our life, you know that! We will never fail you.”

“Ah, I know that’s true, you three have never disobeyed me; but you can’t help me, my dear children. Little girls! Nothing but girls, alas! Only a boy could get me out of the trouble I’m in. My sweethearts, from childhood on, all you’ve ever learned to handle are spindles and needles: spinning and embroidery are all the tasks you know. Only a hero can save me now – a young man who can whirl a heavy weapon – brandish a sword – gallop at the foe like a dragon at lions!”

His daughters cried out, “What are you hiding from us? Speak!” They threw themselves on their knees before him and the emperor gave in. “My children, this is why I’m sad. When I was young, no one dared touch my empire, but the years have frozen my blood and drunk my strength. My enemies are no longer afraid of me: foreign soldiers will set fire to my roofs and water their horses at my wells. There’s nothing to be done, I must submit to the All-Powerful Emperor, as all other emperors on earth have done before me. But he makes all his vassals send the best of their sons to serve ten years in his court, and I have no sons, only three daughters.”

“So what? I’ll go!” cried the eldest, “I’ll save you!”

“No, poor child, it’s useless!”

“Father, one thing is sure, you shall never be ashamed of me. Am I not a princess, and daughter of an emperor?”

“Very well. Get yourself ready and you may try.”

The gallant girl jumped for joy and rushed to prepare for her journey. She turned coffers upside down and emptied chests, packing enough gold-embroidered garments and fine jewels for a year, with all kinds of provisions. She took the most spirited horse from the royal stables, a splendid steed with fiery eyes, silken mane and silver coat.

When her father saw her armed and mounted, making her horse prance in the courtyard, he gave her the best advice, telling her all kinds of tricks to disguise her true sex and warning her against gossip and indiscretions so that everyone would believe she was a young prince chosen for an important mission. Finally he said, “Go with God, my daughter, and keep my advice tucked safely between your two ears.”

Horse and rider leaped away. The princess’s armour shone like a flash of lightning in the eyes of the stunned guards: she split the wind and was gone in the blink of an eye. And if she hadn’t slowed down for her retinue of boyards and servants, they would have been lost, unable to catch up. But although she didn’t know it, her father the emperor – who was a magician – wished to test her. Hurrying ahead of her, he threw a copper bridge over the way, changed himself into a wolf with fiery eyes, and crouched under the arch. As his daughter came by, the wolf leaped howling from under the bridge, teeth gnashing and rushed at her, as if to tear her apart.

The poor girl’s heart leaped with fright, the horse gave an enormous bound – and in panic she wrenched him around, spurred him away and didn’t stop till she was back at her father’s palace.

The old emperor had got back before her. He came to meet her at the gate and shaking his head sadly, welcomed her with these words, “Didn’t I tell you, my little one, flies can’t make honey?”

“Alas, father, how was I to know that on my way to serve an emperor I would have to fight raging wild beasts?”

“There, stay by the fireside with your needle, and may God have pity on me! He alone can spare me from shame.”

Now the second princess came to ask permission to attempt the adventure, swearing that she would stop at nothing to see it through. She begged so hard that her father let her have her way, and off she went, all armed, followed by her baggage train. But she too met the wolf barring the way at the copper bridge, and returned discomfited just like her older sister. The old emperor received her in the same way in front of the gate and said sadly, “Didn’t I say to you, little one, not every bird can be caught?”

"But father, this wolf was really scary. He opened his jaws so wide he could have swallowed me in one gulp, and his eyes flashed rays of lightning as if to destroy me on the spot!’”

“Then stay by the fireside, embroider cloth and make bread. May God help me!”

But here comes the youngest daughter:“Father, it’s my turn. Let me too try my luck. Perhaps I shall laugh at the wolf!”

“After what happened to the others? You have a nerve, you baby! How dare you talk about laughing at the wolf? You’re hardly old enough to use a spoon!"

The old emperor did everything he could to dissuade her, but it was no good. “For you, father, I’d chop the devil into pieces – or turn devil myself. I feel sure I’ll succeed, but if God is really against me, at least I’ll come back with no more shame than my sisters.”

Her father continued to hesitate, but his daughter coaxed him so sweetly that he was beaten. “Very well, I shall let you go. How much use it will be, we shall see. At least I shall have a good laugh when I see you coming back, head hanging, and staring down at your pretty little slippers.”

“Laugh if you wish, father, I shall not be dishonoured.”

The first thing the girl decided to do was to go to an old, white-haired boyard for advice – and remembering the stories she’d heard of the deeds of her father when he was young, she thought of his warhorse, which reminded her she needed to pick one for herself. So she went to the stables and looked in every stall, with her nose in the air. The best horses and mares in the empire – not one of them pleased her. Finally, after a long search, she found the famous horse of her father’s youth, a hairless, broken-down old nag lying in the straw. The girl gazed at him in pity, unable to move away. Then the horse spoke:

“How sweetly you look at me! If only you’d seen me as I was on the battlefield, when your father and I won glory together! but now I’m old, no one rides me any more. See how dry my coat is? My old master neglects me, but if someone cared for me properly, I’d be better than the ten best horses in the stable.”

“How should you be cared for?” the young woman asked.

“Sponge me down morning and evening with rainwater, give me barley boiled in new milk, and most important of all, ginger me up with hot cinders.”

“I’ll do it, if you’ll help me in my plans.”

“Mistress, you won’t regret it!”

The princess did everything the magical horse had asked. On the tenth day, a long shiver ran through his hide. He was glossy as a mirror, fat as butter and agile as a mountain goat. Looking joyfully at the young woman, he kicked up his heels and said, “May God bring you happiness and success, for you’ve given me new life. Tell me your plans! Command, and I obey!”

The king’s daughter made ready for the journey. Instead of weighing herself down with a year’s provisions like her sisters, she gathered together some plain, loose-fitting boy’s clothes, underwear and food, with a little money in case she needed it. Then she caught her horse and came before her father. “God and his saints protect you, my dear father, and keep you safe till I return!”

“Bon voyage, my child! Just remember my advice: turn to God in every danger. Only he can bring you aid.” The young woman promised, and off she went.

Now, just as he’d done before, the emperor hurried ahead, flunga copper bridge over the way, and waited. But before she got there, the magical horse warned the princess what tricks her father was up to, and told her how to get out of it with honour.

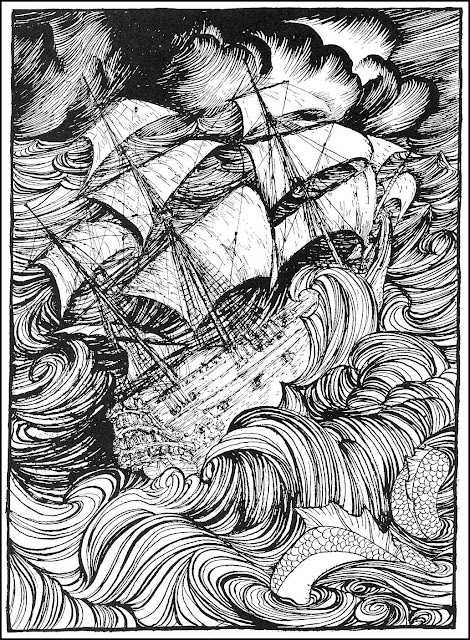

As soon as she arrived at the copper bridge, the wolf leaped at her – flaming eyes, raging teeth, mouth like an oven, tongue like a firebrand – but the gallant girl spurred her horse and rushed at him, sword flashing – and she would have split him down the middle from nose to tail if he hadn’t recoiled and run away. She wasn’t playing, that girl! Her strength came from God and she was determined to accomplish her task. Then, proud as she was brave, she crossed the bridge. Delighted with her courage, her father took a short cut. At the end of the next day’s march, he threw a silver bridge across the way, turned himself into a lion and lay in wait. But the horse warned his mistress of this trick, too. As soon as she arrived at the silver bridge, out jumped the lion, covered in spiny hair. His teeth were like cutlasses, his claws like knives, and he roared loud enough to uproot forests and make your ears bleed. The princess caught her breath – but she charged the lion, sword raised, and dealt a blow of such force that if he hadn’t twisted aside she would have cut him in quarters. Then she crossed the bridge in a single leap, praising God.

But her father got ahead of her again. Three days’ march ahead he threw a golden bridge over the way, turned himself into a dragon with twelve heads and hid beneath the arch. When the princess came in sight, the dragon leaped into view. His tail clattered and coiled, smoke billowed from his fiery jaws, and his twelve tongues waggled and wove about, covered in bristles. The young woman’s heart nearly failed, but the horse urged her on: she raised her sword, spurred forwards and fell upon the dragon. They fought fiercely for an hour until, striking sideways with all her force, she slashed off one of the monster’s heads. He roared to crack the sky, did three somersaults and disintegrated in front of her, taking on human shape.

Even though the princess had been warned, she could scarcely believe it was her own father, but he embraced and kissed her, saying, “Now I see that you are as brave as the bravest! And you’ve picked the right horse; without him you would have fared like your sisters. Now I believe you will fulfil your mission. Remember my advice, and above all, listen to the horse you’ve chosen.” She knelt for his blessing and they parted.

On she went till she came to the mountains that hold up the roof of the world. Here she came across two genies who’d been fighting to the death for two years, neither one of them managing to overcome the other. Assuming her to be a young hero riding out on adventure, one of them cried, “Hey, Fet-frumos, help me! And I’ll give you a horn which can be heard for a distance of three days journey!”

The other shouted, “No – help me, and I’ll give you my precious horse Sunray!”

The princess quickly consulted her own horse. “Take the last offer,” he advised. “Sunray is my younger brother, and even wiser and more active than myself.” So the princess hurled herself at the other genie and split him in half from the skull to the belly-button.

The genie she’d rescued thanked and embraced her (noticing nothing strange), and together they went to his house so that he could give her Sunray as he’d promised. Here the genie’s mother greeted them, delirious with joy to see her son safe and sound. Hardly knowing how to thank him, she kissed the young champion – and immediately suspected something. Still, she showed ‘him’ to the best chamber – but the princess insisted on tending to her horse first. And in the stables, the horse told her everything she needed to know.

For the old woman was brewing up mischief. She whispered to her son that this handsome young fellow was really a young woman – and just the sort to make him an excellent wife. The genie didn’t believe her. Never! Ridiculous! No mere woman could handle a sword like that. But his mother persisted, and promised to prove it. That evening, at the head of each bed, she placed a magnificent bunch of flowers, enchanted so that it would wither overnight at a man’s bedside, but stay fresh at a woman’s.

During the night, the young woman got up (as the horse had advised), tiptoed into the genie’s bedroom, lifted the already-withered bunch of flowers, and slipped her own still-fresh one into its place, knowing that its beauty would soon fade. She went back to her room, lay down and slept. Early next morning the old woman rushed to her son’s room and found the flowers withered, as she’d expected. Next she went to the girl’s room, and was shocked to find those flowers equally faded. But she still couldn’t believe her guest was a boy.

“Can’t you see?” she said to her son. “What man has so graceful a figure? That blonde hair, those lips as red as cherries, those bright eyes, those delicate wrists and feet? This simply has to be a young noblewoman dressed up in armour!”

So they dreamed up a second test. Next morning the genie took his young friend’s arm and suggested a walk in the garden. He showed off all his flowerbeds, and invited ‘him’ to pick any or all of them. But warned by the horse, and suspecting a trick, the king’s daughter demanded roughly why they were idly discussing flowers, when there was man’s business to be done – the stables to visit, horses to tend? So the genie swore to his mother that their guest was certainly a boy. Yet still his mother obstinately judged otherwise.

For the last test, the genie showed the girl into his armoury, full of rows of scimitars, bayonets, maces and sabres – some plain and simple, others decorated with jewels – and invited her to choose one. The princess looked at them, carefully testing the points and edges. Then like a practised warrior, she thrust into her belt an old rusty Damascus blade, curved like a crescent, and told the genie she was leaving and it was time to give her Sunray. Seeing her choice of weapon, the old woman despaired of ever learning the truth, though she was sure in her own mind of what she’d told her son – that this was a clever and tricky girl. But they had to do as she wished. They went to the stables and gave her the horse, Sunray.

The emperor’s daughter leaped on Sunray’s back and pressed him to run faster and faster. Galloping alongside, her father’s old horse said to her, “Mistress, now you must go on with my young brother. Trust him as you do me. He is like myself, but younger and more vigorous. Sunray can show you what to do in difficult times.” Then with tears in her eyes the girl dismissed her old horse, the horse of her father’s youth.

She journeyed on, when all of a sudden she saw a bright curl of golden hair lying in the road. Pulling Sunray to a halt, she asked if she should pick it up or leave it. Sunray answered, “If you take it you’ll be sorry, but if you don’t take it you’ll still be sorry: so take it.” She picked it up, stuck it into the collar of her tunic and rode on. They went by mountains and valleys, through dark forests and sunny meadows, they passed over springs of fresh water, they came to the court of the All-Powerful Emperor, where the sons of other emperors served him like pages. The Emperor was delighted to see this spirited young prince and soon appointed him as a personal companion. This made the other pages jealous. Spotting the lock of shining golden heir tucked into the collar of his shirt, they went to the emperor and told him that their new companion had been boasting that he knew where Iliane lived, golden Iliane, beautiful Iliane of that song,

Tresses of gold,

The fields grow green,

The roses blossom…

and that he’d shown them a lock of her golden hair. As soon as he heard that, the All-Powerful Emperor ordered the girl to be called before him.“Fet-Frumos, you’ve deceived me. Why did you hide from me that you know Iliane of the Golden Hair? How did you steal that curl? Bring her to me, or your head will roll where your feet are now. I have spoken.”

All the poor young woman could do was bow and retreat, but when Sunray learned what had happened, he said, “Don’t worry! A genie has kidnapped Iliane, whose golden hair you picked up on the road, and imprisoned her in the Swamps of the Sea. She refuses to marry her kidnapper unless he can round up her stud of mares, which is a dangerous thing to do. Go back to the All-Powerful Emperor and say you need twenty ships, and a cargo of precious goods to put in them.

’

The girl went straight to the emperor. “Son,” said the emperor, “you shall have all of it! But bring me Iliane of the golden hair.”

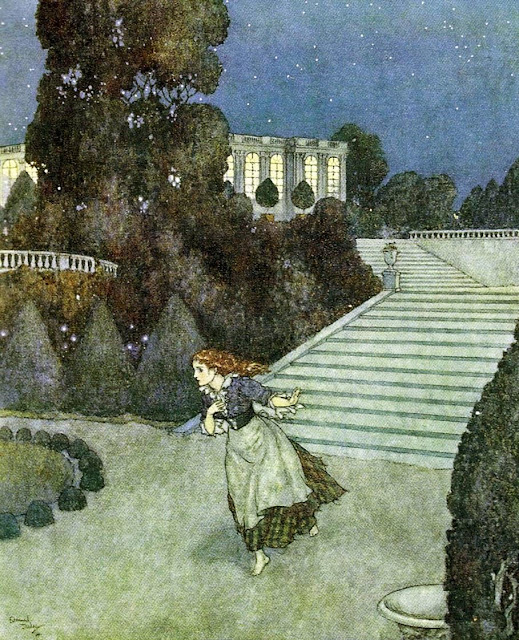

Well, neither wind nor waves delayed them. After a voyage of seven weeks to the Swamps of the Sea, they came to the coast of a beautiful island all covered in revolving palaces, castles which turned around by themselves so as always to face the sun. The emperor’s daughter disembarked, and taking some bejewelled slippers she rode towards the castles on Sunray, where three of the genie’s eunuchs who were guarding Iliane, came to meet her. (The genie was away from home trying to round up Iliane’s mares, leaving only his old mother in charge.) The girl told them she was a merchant who had lost his way in the sea marshes, and had luxury goods to sell.

Now looking from her window, Iliane had spotted the handsome merchant already. Her heart gave a sudden thump at the sight of him, and she persuaded the genie’s mother to let her go down and try on the wonderful slippers. They fitted perfectly, and when the youth told her that his ships held even finer and more precious things, she went on board. While she was looking at all the enchanting merchandise (and exchanging glances with the young merchant) she didn’t notice the shore receding and the sea spreading out over the swamps so far, so far, that soon there was no sign on the horizon of the island and the coast. A good wind blew, the ships flew like seabirds, and beautiful Iliane of the golden hair found herself in the middle of the sea, but did she care? Not when she lifted her eyes to the face of the young merchant who had delivered her from prison.

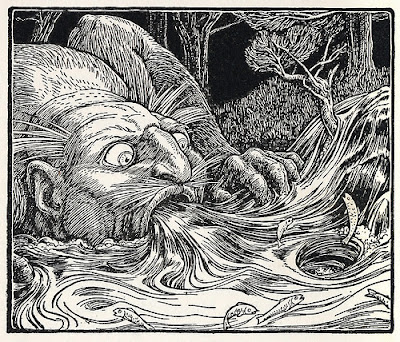

Nearly had they reached the opposite shore when they saw the genie’s mother rushing after them. Wading over the blue billows, hopping from wave to wave, one foot in the air and the other on the splashing foam, she was almost on their heels, flames streaming from her mouth. The instant the ship touched land they leaped ahore, and the emperor’s daughter threw Iliane up on to Sunray’s back. She leaped up herself, told Iliane to hold to her waist – and away they galloped with the old crone’s breath hot on their shoulders. “I’m scorching!” Iliane cried.

So the emperor's daughter leaned down to the horse and asked him what to do; and Sunray answered, “Reach into my left ear, pull out the sharp stone you’ll find there and throw it behind you!”

The emperor’s daughter did just that. Then all three of them began to race like a hurricane, while behind them in one stroke a rocky mountain rose up to touch the sky. But the genie’s mother flung herself at it, hoisting herself from rock to rock. Look out! Beware!

Twisting around, Ilaine saw her coming. In fright she buried her head in the young merchant’s neck, covering it with kisses and crying out that they would be overtaken. Again the girl bent over the horse’s neck and asked him what to do, for the flames jetting from the witch’s mouth were burning their waists.

“Reach into my right ear, pull out the brush you’ll find there and throw it behind you!”

The emperor’s daughter did just that. Then they ran harder than ever, while behind them sprang up a vast, dark forest, too thick for even the tinest animal to thread its way through. But the crone swung herself through the trees, crushing them, clutching their branches in a burning grip, shoving and shaking their trunks, and after them she came, onwards, onwards, whirling like a tornado.

Iliane saw her coming and, her head buried in the merchant’s neck which in her terror she was now both kissing and biting, she sobbed out her fear of being caught, which was surely now a certainty.

For the last time the girl bent over the horse's neck and asked him what they should do, for the crone was spitting out a column of fire and frizzling the golden hair on their heads. And Iliane was writhing in pain, and Sunray gasped, “Quick, take the ring from Iliane’s finger and throw it behind you!” And this time, up shot a stone tower, smooth as ivory, strong as steel, bright as a mirror, tall enough to crack the sky.

Raging and cursing, the genie’s mother gathered her strength, bent like a bow, and shot herself up to the top of the tower; but she fell through the hole of the ring, which formed the tower’s turret, and couldn’t climb out again; all she could do was cling with her claws to the niches and crannies, with no hope of climbing up or getting out. She did everything she could, she shot out flames for a distance of three hours travel, hoping to grill the fugitives; but barely a spark fell at the tower’s foot where the two lovers were snuggled. And the witch kept puffing out fiery sparks and set fire to the countryside for leagues around, for she could hear her enemies laughing and hugging and taunting her, till in her final rage she crumbled to bits and died. Then the tower bowed gently down to the handsome young merchant, who put his finger through the ring as Sunray had told him, and the high tower vanished as if it had never been there, and there was the handsome girl’s finger with the ring around it. And off they darted like mountain eagles till they came to the imperial court.

The All–Powerful Emperor received Iliane with great respect. He could hardly contain his joy; he fell in love with her at first glance,and decided to marry her. But Iliane was depressed and saddened; she longed to be like other girls who could do as they wished. Why did her fate seem aways to be in the hands of those she disliked – genie or emperor – while her heart was given to the handsome young merchant of the island?

She replied, “Glorious emperor, may you rule your people in honour forever! Alas, I am forbidden even to dream of marriage until someone rounds up my herd of mares and their fierce stallion.”

At this, the All-Powerful Emperor called the warlike girl and gave the order, “Fet-frumos, fetch me this herd of mares, along with their stallion. If you don’t, I will cut off your head.”

“Dread emperor, I kiss your hands. You have put my head in danger already, sending me on a dangerous task, and now you’re giving me another. I see plenty of valiant sons of emperors here, with nothing to do; it would be fairer to send someone else on this errand. What will become of me, where will I find this herd of mares you order me to fetch?”

“How should I know? Ransack heaven and earth if you must, but I’m telling you to do it, and don’t dare to utter a word!”

The girl bowed. Off she went to tell Sunray everything, and the wise horse answered, “Find me nine buffalo hides, cover them in pitch, spread them over my coat and don’t be afraid, for with God’s help you will succeed in this mission; but believe me, mistress, in the end he’s going to play you false.”

She did just what the horse had told her and the pair of them set out. It was a long, hard journey, but at last they came to the region where Iliane’s herd of mares was to be found. Here wandered the genie who had stolen Iliane. He thought she was still in his power under strong guard, but since he had no idea how to perform the task she’d set him he spent his time went running here and there after Iliane’s horses, not knowing what saint to call upon for help and generally exhausting himself. When the heroic girl told him that Iliane was gone from the revolving palace and that his mother had died of spite, the genie became fire and flame and flung himself upon her. They fought together till the ground shook and the noise terrified the birds and beasts for twenty leagues around. Finally, with a mighty effort, the girl chopped off her enemy’s head, left the carcase to the crows and magpies, and found the plain where the mares were running.

Sunray now told his mistress to climb a tree and watch what happened. Armoured in the nine buffalo hides, the splendid horse whinnied three times and the whole herd of mares came running to him with their stallion – who was white with foam and roaring in anger. The stallion leapt at Sunray, but with each bite he tore away only a mouthful of buffalo hide, while every time Sunray bit him, he tore away a mouthful of flesh. When the stallion sank down, bleeding and conquered, Sunray hadn’t suffered a scratch, but his buffalo-hide armour hung in tatters. Then the emperor’s daughter came down from her tree, mounted him and led the herd away to the All-Powerful Emperor’s court, where Iliane came and called all of the mares to her by their names. And as soon as he heard her voice, the wounded stallion was healed and looked as fine as he had before, without even the tiniest scar.

Iliane now told the All-Powerful Emperor he must have her mares milked, so that he and she could be betrothed by bathing in their milk. Yet who could do this? The mares kicked fiercely at anyone who came near; even a single kick could cave in your chest, and no one could touch them. The Emperor ordered ‘Fet-Frumos’ to get on with it and do the job.

The emperor’s daughter felt a darkness in her soul. Was she always to be given the hardest tasks? She would collapse under the strain if this went on! Fervently she prayed God to help her, and since she was pure in both body and soul, her prayer was answered. It began to rain – the sort of rain that comes down in buckets. Water rose as high as the mares’ knees, froze to ice as hard as stone and locked their legs in place. The girl thanked God for this miracle and began milking the mares as if she had been doing so all her life.

But by now the All-Powerful Emperor was almost dying of love for Iliane. He kept staring at her the way a child stares at a tree covered in ripe cherries, but she used all kinds of tricks to put off the day of their marriage. Finally running out of ideas, she said, “Gracious emperor, you have granted my wishes, but I would like one little thing more, after which we shall be married. Get me the flask of holy water which is kept in a little chapel beyond the river Jordan. Then I will become your wife.”

The All-Powerful Emperor summoned Iliane’s rescuer and said, “Go, Fet-Frumos, and don’t come back without the flask of holy water, or I will cut off your head.”

The young woman withdrew with a heavy heart, but when Sunray heard what had happened he said, “Dear mistress, here is the last and hardest of your tasks. Keep up your faith in God! Time is nearly up for this wicked and abusive emperor. The flask of holy water stands on an altar in a little chapel guarded by nuns, who sleep neither night nor day. However, from time to time a hermit visits them, to instruct them in holy things. A single nun remains on guard while they listen to his words, so if we can pick that very moment, all will be well. If not, we’ll have plenty of time to regret it.”

Away they rode. They passed over Jordan river and came to the chapel just moments after the hermit had arrived and called the nuns to chapter. A single nun remained on guard, but the hermit’s lesson went on for so long that, tired out by the endless watch, she lay down over the threshold and went to sleep.

Soft as a cat, the emperor’s daughter stepped over the the sleeping nun. Stealthily she lifted up the holy flask, leaped on her horse and galloped away! The clatter of Sunray’s hoofs woke the nun. She saw the flask was gone and began to wail and cry. The other nuns came rushing. Seeing the rider disappearing at top speed and realising there was nothing to be done, the hermit fell on his knees and called down a curse upon the thief: “Thrice holy Lord, grant that the wretched knave who has stolen the holy flask of thy baptismal water may be punished! If it is a man, may he become a woman! – or it is a woman, may she become a man!”

But see how the hermit’s prayer was answered! When the emperor’s daughter suddenly felt herself a gallant boy in both body and soul, just as she had always seemed, she was neither astonished nor upset. In fact, the thoughts of this new he flew straight to Iliane… Delighted with the transformation, hardier and bolder than ever, the youngster returned to the All Powerful Emperor’s court and handing the flask over, said, “Mighty emperor, I salute you. I have completed all the tasks you set me; I hope this will be the last of them. Be happy then, and reign in peace, as you hope to receive mercy from our Lord!”

“Fet-frumos, I am pleased with your services! After my death you shall succeed me on the throne, as up till now I have had no heir. But if God gives me a son, you shall be his right hand,” the Emperor replied.

But Iliane Goldenhair was very angry that this last wish of hers had been fulfilled. She decided to take revenge on the Emperor for always handing the hardest tasks to the invincible young hero she loved. She thought that if her royal admirer was sincere he ought to have fetched the flask of holy water himself. So she ordered a bath of her mares’ milk to be heated, and asked the All-Powerful Emperor to bathe in it with her – he agreed with delight. Once they were in the bath together, she had the stallion from her herd brought in to blow cool air on them. At her signal, the stallion blew cool air upon Iliane through one nostril – and through the other he blew a blast of red-hot air at the All-Powerful Emperor. It was so fierce it charred him to the bone, and he fell back dead.

There was great confusion in the land at the strange death of the All-Powerful Emperor! From all sides they assembled, crowds ran to witness his magnificent funeral.After that, Iliane said to the youth,

“You brought me here, Fet-Frumos: you rounded up my herd of mares with their stallion and all the rest, you killed the genie, and the witch his mother, you brought me the flask of holy water from beyond the Jordan. My life and love belong to you. Be my husband! Let us bathe together and marry!"

“Yes, I’ll marry you, because I love you and you love me,” the youth answered in a voice just as soft as when he was a girl,“but know that in our house, the cock will crow and not the hen…” And guess what? Just because he was a man now, he added, “I’ll have my way!” So they were married, and reigned with justice and in the fear of God, protecting the poor, maltreating no one, and if they haven’t died yet, he and Iliane are reigning still.

And I was there at the wedding, indeed I was! I stood around gaping at all of the parties, for nobody dreamed of offering me a chair. So what did I do?

I sat on my saddle like any old farmer

And I told you the story of the princess in armour.

More about fairy tales and folklore in my book "Seven Miles of Steel Thistles" available from Amazon here and here.Picture credits:The Princess Charges the Lion, by H J Ford, illustration for The Violet Fairy BookThe Valkyrie Lagerta, by Morris Meredith Williams, 1913