This is a story about something that happened long ago when your grandfather was a child. It is a very important story because it shows how all the comings and goings between our world and the land of Narnia first began.

In those days Mr Sherlock Holmes was still living in Baker Street and the Bastables were looking for treasure in the Lewisham Road…

The Magician’s Nephewis unique among the Narnia stories in that a large proportion of the narrative – more than half – takes place outside Narnia. (This may be why in the second sentence Lewis reassures the anxious reader that the book will eventually get there.) First he locates the story in the real past ‘when your grandfather was a child’ and, immediately after, in the fictitious past of Sherlock Holmes and the Bastable children. Why?

Partly it’s shorthand. Any child who’d read E Nesbit’s books (and in the 1950’s and 60’s most of us had) would feel instantly at home in the London parts of the narrative. There are strong similarities between TMN and Nesbit’s books – especially her 1906 novel The Story of the Amulet which Lewis had read and loved as a boy. (‘It first opened my eyes to antiquity, the “dark backward and abysm of time”. I can still re-read it with delight.’) These similarities are not restricted merely to period and style. Both books involve the use of a magical token to travel into other worlds: travel in time (The Amulet) or between universes (TMN). In particular, Lewis borrows and re-interprets Chapter 8 of The Amulet,in which Nesbit’s children struggle to control and entertain a Babylonian Queen in Victorian London. More of that later.

Despite this, TMN is a very different kind of book from E Nesbit’s. No matter what scrapes her characters fall into, their world is essentially a safe one. It’s impossible to imagine anything truly bad happening to them. Yes, the Bastable children have lost their mother as Digory fears to lose his. It is, however, a fait accompli that does not affect the reader and Oswald Bastable gets it briefly out of the way. ‘Our mother is dead, and if you think we don’t care because I don’t tell you much about her you only show that you do not understand people at all.’ The Story of the Treasure Seekers is not about loss: the Bastables’ emotions are not on show.

‘Happy, but for so happy ill secured’ runs the epigraph from Milton that heads the first chapter of Lewis’s autobiography, Surprised By Joy. The chapter ends:

With my mother’s death all settled happiness, all that was tranquil and reliable, disappeared from my life. There was … no more of the old security. It was sea and islands now; the great continent had sunk like Atlantis.

‘Like Atlantis’ – the metaphor is striking but strange. Could it, I wonder, have been drawn from Chapter 9 of The Amulet, in which the children visit Atlantis and barely escape as a great wave swamps the city and the mountain bursts into flame? As their friend the ‘learned gentleman’ looks back though the arch of the Amulet, he sees ‘nothing but a waste of waters, with above it the peak of the terrible mountain with fire raging from it.’ If, as is possible, this image made a deep impression on Lewis’s childhood imagination, it’s no wonder TMN, which engages so closely with the trauma of his mother’s illness and death, borrows from The Amulet in imagery and style.

One morning [Polly] was out in the back garden when a boy scrambled up from the garden next door and put his face over the wall. … The face of the strange boy was very grubby. It could hardly have been grubbier if he had first rubbed his hands in the earth, and then had a good cry, and then dried his face with his hands. As a matter of fact, this was very nearly what he had been doing.

With The Magician’s Nephew Lewis remembers, rewrites, reclaims his own past. It is a myth of healing, a poetic re-imagining, a fairytale in which the universe turns out not, after all, to be impersonal and unkind. Its emotional core is not the wondrous creation of Narnia but Digory’s approaching personal tragedy. He is in tears when we meet him: his happiness is ill secured. The line comes from Book 4 of Paradise Lost, when Satan arrives in Eden and views Adam and Eve in their short-lived innocence:

Ah! gentle pair, ye little think how nigh

Your change approaches, when all these delights

Will vanish, and deliver ye to woe –

More woe, the more your taste is now of joy:

Happy, but for so happy ill secured

Long to continue…

The Magician’s Nephewworks so well because Digory’s grief is truly felt. But it’s possible that Lewis’s first-page references to the world of Sherlock Holmes and the Bastables deliver a sub-textual, maybe even unconscious warning. This story, like theirs, is fiction. For young Jack Lewis and his mother there was no miracle. The things that happen to Digory Kirke are not the sorts of things that happen in real life.

With new characters and new setting there is a brisk, fresh energy to the narrative. The first four pages (three, minus the illustrations) are a brilliantly economical bit of scene-setting. By the end of them we know everything we need to know about Polly and Digory, and Digory’s Uncle Andrew, mad Mr Ketterley. Within another page or so, Polly is showing Digory her den in the attic, a dark place behind the cistern.

Here she kept a cash-box containing various treasures, and a story she was writing and usually a few apples. She had often drunk a quiet bottle of ginger-beer in there: the old bottles made it look more like a smugglers’ cave.

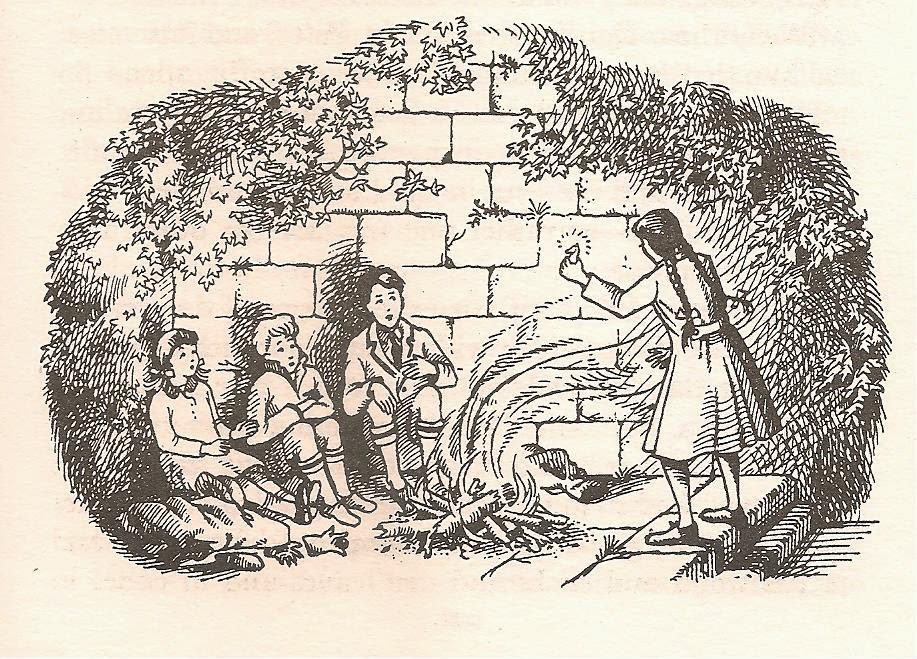

![]()

Polly is tough, practical and confident, with a strong sense of self-respect. She is an excellent partner for the impulsive and more emotional Digory. In a 1998 article for The Guardian entitled ‘The Dark Side of Narnia’, Philip Pullman has complained that Lewis (among other crimes) is guilty in the Narnia books of sending the message ‘boys are better than girls.’ Possibly it’s not quite fair to take someone to task for an opinion in a newspaper article written so long ago, and some of Pullman’s accusations are justifiable, but hardly this one. I cannot see it and never have. To base an accusation of sexism on ‘the problem of Susan’ alone is to ignore the strength of such different characters as Lucy, Jill, Aravis and Polly – who are all gallant, courageous and memorable. I wonder how recently Mr Pullman had read the books.

A little girl myself, I certainly didn’t feel excluded or denigrated. The easy, bickering comradeship between Polly and Digory was just what I was used to from E Nesbit’s books. Moreover, Polly sounded just like me. I wrote secret stories! With my brother, I loved to make dens – in hedges, cupboards, in corners of the playground, in barns, attics, sheds and lean-to’s, in patches of waste ground, on building sites. (Pacing stilt-like, ten feet up, across the open floor-joists of a half-completed house, my brother fell across them, scraping his ribs. We didn’t confess.)

Just as the Bastables, in The Treasure Seekers, play at being detectives and spy on the empty house next door, Polly and Digory decide to explore further down the attic tunnel, hoping to come out in the abandoned house next door but one. They try to calculate how far they will have to go, and I don’t notice any nonsense about boys being better than girls. The children are equally and endearingly erratic with their sums: ‘They both got different answers to it at first, and even when they agreed I am not sure they got it right. They were in a hurry to start the exploration.’

However, their mistake leads them to emerge in the wrong house.

It was dead silent. Polly’s curiosity got the better of her. She blew out her candle and stepped out into the strange room.

With Polly in the lead, we look around. The room is full of books. A fire is burning in the grate. A high-backed armchair faces it, with its back to us. On a bright red wooden tray is a collection of shiny yellow and green rings, in pairs. And the room is quiet:

…so quiet that you noticed the ticking of the clock at once. And yet, as [Polly] now found, it was not absolutely quiet either. There was a faint – a very, very faint – humming sound. If Hoovers had been invented in those days Polly would have thought it was the sound of a Hoover being worked a long way off – several rooms away and several floors below.

Lewis’s asides to the reader never divide us from the narrative, they pull us in. We’re there, holding our breath, listening to the quietly ticking clock – which is ordinary – and to the almost sub-acoustic humming which is strange. The comparison of the sound to a vacuum cleaner being run ‘a long way off’creates unease in two ways: it can’t be a vacuum cleaner, and it directs our attention to the remoteness of this attic room at the top of the house, its distance, rooms and floors away, from the safe and ordinary world of cleaners and household tasks. It’s an almost cinematic build-up of tension, and in classic horror-film style Lewis allows us and his characters to take one breath – before springing the trap. ‘It’s all right, there’s no one here,’ Polly says. Then –

The high-backed chair in front of the fire moved suddenly and there rose up out of it – like a pantomime demon coming out of a trap door – the alarming form of Uncle Andrew.

Digory was quite speechless … Polly was not so frightened yet; but she soon was. For the very first thing Uncle Andrew did was to walk across to the door of the room, shut it, and turn the key in the lock. Then he turned round, fixed the children with his bright eyes, and smiled, showing all his teeth. ‘There!’ he said. ‘Now my fool of a sister can’t get at you!’

This is truly frightening – in fact I think it frightens me more now than it did when I was ten. With his clean-shaven face, sharply-pointed nose and tousled mop of grey hair, tall thin Uncle Andrew – who behaves in ways, as Lewis puts it, ‘dreadfully unlike anything a grown-up would be expected to do’ – now strikes me as a kind of ur-Jimmy Savile.

Compare the situation in The Story of the Amulet, where the children consult the elderly scholar who lives upstairs about the inscription on their Amulet.

‘There’s a poor learned gentleman upstairs,’ said Anthea, ‘we might try him. He has a lot of stone images in his room, and iron-looking ones too – we peeped in once when he was out.’

There are no surprises. The children are in control. Their ‘learned gentleman’ is no threat. Not so here. Though it wasn’t spelled out, in the 1950s, just why you should never get into cars with strange men, and I doubt CS Lewis intended anyone reading this passage to think ‘child-molester’, there is no doubt at all that Digory and Polly are in serious and as yet unspecified danger. The cloud of possibilities is terrifying.

Digory is more frightened than Polly, in this passage – and Polly is more easily fooled. Is this because she is a fool? No. The difference between the children, here and right through the book, is that Polly possesses the as-yet-untested confidence of an ordinarily happy childhood. There’s something pathetic and innocent about her plea to Uncle Andrew: ‘Please, Mr Ketterley. It’s nearly my dinner time and I’ve got to go home. Will you let us out, please?’ But Digory has already been hurt by life. His mother is dying, he knows that awful things can and do happen: his plea acknowledges the danger and answers it with a threat: ‘Look here… it really is dinner time and they’ll be looking for us in a moment. You must let us out.’

Uncle Andrew appears to capitulate. For Polly, this is the universe righting itself after an alarming wobble. He offers her one of the pretty yellow rings and she is ready to trust him, but Digory sees ‘an eager, almost a greedy look’ on his uncle’s face.

‘Polly! Don’t be a fool!’ he shouted. ‘Don’t touch them.’

It was too late. Exactly as he spoke, Polly’s hand went out to touch one of the rings. And immediately, without a flash or a noise or a warning of any sort, there was no Polly. Digory and his uncle were alone in the room.

All that, in just the first chapter, perhaps eleven pages all told.

This has been strong stuff. At this point in the narrative Uncle Andrew is far scarier than the White Witch or the Green Lady or even Queen Jadis – and the reason is because he is so much more plausible. Children don’t expect to meet Witch Queens, but eccentric adult relations are two a penny. This must be why, through the rest of the book, CS Lewis transforms Uncle Andrew from a nightmare Jack-in-the-box to a drenched and muddy figure of fun a child can only laugh at. As soon as Uncle Andrew embarks on justifications of his behaviour, he begins to be pompous, selfish and manipulative, but less frightening. When he emotionally blackmails Digory to go after Polly into the unknown, Digory loses his fear and delivers a searing rebuke the equal of Puddleglum’s to the Green Witch.

‘Very well. I’ll go. But there’s one thing I jolly well mean to say first. I didn’t believe in Magic till today. I see now it’s real. Well if it is, I suppose all the old fairytales are more or less true. And you’re simply a wicked, cruel magician like the ones in the stories. Well, I’ve never read a story in which people of that sort weren’t paid out in the end, and I bet you will be. And serve you right.’

Digory has the moral high ground and the upper hand: his words are an implicit promise that good will prevail: from this point on Uncle Andrew is more of a nuisance than a bogeyman.

The Wood Between the Worlds is a marvellous creation. It isn’t ‘Aslan’s country’: it’s not at all like the high, wooded mountain top of The Silver Chair with its bright birds and clear air. ‘It was the quietest wood you could possibly imagine. … You could almost feel the trees growing.’ This is a place of no names, a ‘dreamy, contented’ place in which, if you linger, you are in danger of losing your identity. When the children see one another they have already forgotten who they are. ‘Have you been here long?’ Digory asks.

‘Oh, always’, said the girl. ‘At least – I don’t know – a very long time.’

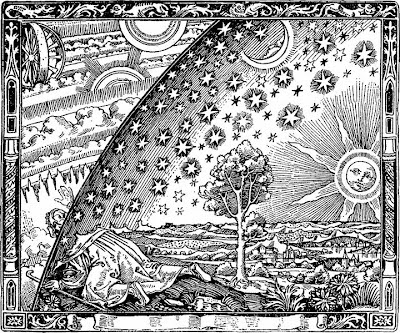

If The Wood Between the Worlds has a literary antecedent, it is the ‘the wood where things have no names’ in ‘Alice Through the Looking Glass’.

[Alice] was rambling on in this way when she reached the wood: it looked very cool and shady. ‘Well at any rate it’s a great comfort,’ she said as she stepped under the trees, ‘after being so hot, to get under the – under the – under this, you know!’ putting her hand on the trunk of the tree. ‘What does it call itself, I wonder? I do believe it’s got no name – why, to be sure it hasn’t! … And now, who am I? I will remember, if I can.’ … [But] all she could say, after a great deal of puzzling, was ‘L, I know it begins with an L!’

Wandering on, Alice meets a Fawn. As neither can recall its own identity, they walk trustfully together, Alice’s arms around the Fawn’s neck, until they reach the end of the wood where they regain their names and memories and the Fawn flees in fear. It’s a very short passage, but as a fable of prelapsarian, Edenic innocence it comes with a troubling, perplexing taint: the struggle to remember has a nightmarish flavour and the trust between Alice and the Fawn is based on ignorance rather than innocence. A tree may not need to ‘call itself’ anything, Carroll seems to be saying, but without names we are hardly human. The relief of rediscovery, even with a sting of loss, is palpable.

Though so peaceful, the Wood Between the Worlds too is no place for humans. It is a place where one could drowse forever: and though Digory is here to ‘rescue’ Polly, it is she who sticks to the knowledge of what she’s seen and done. When Digory announces that he, too, has ‘been here forever’, she contradicts him.

‘No you haven’t,’ said she. ‘I’ve just seen you come up out of that pool’.

‘Yes, I suppose I did,’ said Digory with a puzzled air. ‘I’d forgotten.’

Then for a long time neither said any more.

‘Look here,’ said the girl presently, ‘I wonder did we ever really meet before? I had a sort of idea – a sort of picture in my head – of a boy and girl, like us – living somewhere different…’

Then they see the guinea pig with the yellow ring on its back, and the extra stimulus reminds them of who they are and what has happened. Aware now of the danger of the place, Polly insists they must leave. But Digory has a new idea. What if the Wood isn’t any kind of world, but an ‘in-between place’ – like the tunnel in the attic that leads between all the houses in the row at home? Perhaps all the pools in the Wood lead to other worlds. If so, why shouldn’t they visit one?

Here I may add that what Lewis added to Carroll, Diana Wynne Jones borrowed from Lewis: in The Lives of Christopher Chant (1988), the young hero is able to get into other worlds, which he calls ‘Anywheres’, via ‘The Place Between’: an unsettling ‘left-over piece of the world’ full of ‘formless slopes of rock’ with a ‘formless wet mist’ hanging over everything. (Not a place anyone would linger in.) And Lev Grossman’s recent ‘Magicians’ trilogy, in my view a wonderful, adult, fictional commentary on Narnia, presents yet another place of in-between potential: a timeless, empty city reminiscent of Charn, with fountains in place of pools.

There’s a marvellous description of the children testing the rings by changing them over half way back to London: they see:

…bright lights moving about in a black sky; Digory always thinks these were stars and even swears he saw Jupiter quite close – close enough to see its moons. But almost at once there were rows and rows of roofs and chimney pots about them, and they could see St Paul’s … But you could see through the walls of all the houses. Then they could see Uncle Andrew, very vague and shadowy, but getting clearer and more solid-looking all the time…

‘Change!’ shouts Polly, and they rise through the pool back into the Wood. ‘Now for the adventure,’ says Digory. ‘Any pool will do. Come on. Let’s try that one’.

‘Stop!’ said Polly. ‘Aren’t we going to mark this pool?’

I’ve always loved this ‘gasp’ moment as Polly prevents catastrophe: the pools are all alike, the trees are all alike: without marking their pool, how would they ever find it again? How would they ever get home? The shock provokes a brief squabble, after which they try jumping into the new pool and discover by experiment the difference between the yellow and green rings. (The yellow rings draw you towards the Wood. The green rings send you away from it.) On the second try, they find themselves standing in a dull, reddish light, under a black sky, in the ruined city of Charn.

The children have already quarrelled about almost losing the right pool. Now they begin to do so again. Pragmatic Polly wants to leave Charn almost at once on the grounds that there’s ‘nothing at all interesting here’. Digory suggests she’s scared:

‘There’s not much point in finding a magic ring that lets you into other worlds if you’re afraid to look at them when you’ve got there.’

It is of course manipulative, and during this chapter Digory is recognisably his uncle’s nephew – driven by curiosity and the desire to know. After all, just like little Jack Lewis, Digory Kirke will grow up to become a Professor, ‘a famous learned man’. The question is, what sort? Scientist, scholar or magician?

Lewis can hardly disapprove per se of the desire for knowledge, but he asks us to consider the price of it and who pays for it. When Uncle Andrew attempts to justify his actions to Digory, he recounts the story of how he made the yellow and green rings. On her deathbed his old godmother Mrs Lefay (clearly a fairy godmother, and not a nice one) had asked him to find a little box and promise to burn it after her death, unopened.

‘That promise I did not keep.’

‘Well then, it was jolly rotten of you,’ said Digory.

‘Rotten?’ said Uncle Andrew with a puzzled look. ‘Oh I see. You mean little boys ought to keep their promises. Very true: most right and proper, I’m sure, and I’m very glad you’ve been taught to do it. But of course you must understand that rules of that sort, however excellent they may be for little boys – and servants – and women – and even people in general, can’t possibly be expected to apply to profound students and great thinkers and sages. …Ours, my boy, is a high and lonely destiny.’

Lewis has an extraordinary ability to engage his child readers in philosophical and moral questions at a level appropriate to their understanding and without talking down. Children are interested in ethics: much of childhood is spent learning and negotiating the rules. They also have a strong sense of justice. Uncle Andrew’s credo as a Magician is the credo of all those prepared to waive the rules in their own favour, make special exceptions for themselves, and treat ‘lesser’ people as commodities. It’s a fault not limited to magicians: examples can found in the pages of any newspaper. Digory sees right through it. “‘All it means,’ he said to himself, ‘is that he thinks he can do anything he likes to get anything he wants.’”

But his behaviour in Charn demonstrates that he too can be selfish in pursuit of his own way. The children explore the dead and deathly city with its dry fountains and labyrinth of hallways, rooms, arches and stairs – and come at last to the gold doors of the Hall of Statues.

Here Polly takes the lead, just as it was she who stepped first into Uncle Andrew’s attic room. One of the many things I like about this book is the way the children are equally instrumental and/or culpable in taking important decisions. Polly wants to see the magnificent clothes in which the figures are dressed, and Lewis makes it plain these are well worth looking at. I find Polly’s interest in clothes realistic rather than stereotypical: intelligent too, as her first remark demonstrates:

‘Why haven’t these clothes all rotted away long ago?’

‘Magic,’ whispered Digory. ‘Can’t you feel it? I bet this whole room is just stiff with enchantments. I could feel it the moment we came in.’

‘Any one of these dresses would cost hundreds of pounds,’ said Polly.

But Digory was more interested in the faces…

There follows the memorable progression of the faces of the ‘statues’ sitting in their stone chairs. It’s a wonderfully succinct way of presenting the degeneration of an empire or even perhaps of an individual. As the children walk through the room, they see kind, wise faces changing to

…faces they didn’t like … strong and proud and happy, but they looked cruel. A little further on they looked crueller. Further on again they were still cruel, but they no longer looked happy. They were even despairing faces: as if the people they belonged to had done dreadful things and also suffered dreadful things.

It is therefore unnecessary for Digory to exclaim, ‘I do wish we knew the story that’s behind all this.’ His curiosity leads him to examine the golden bell and hammer in the centre of the hall, with its provocative inscription:

Make your choice, adventurous Stranger;

Strike the bell and bide the danger,

Or wonder, till it drives you mad

What would have happened if you had.

Now the children have their most serious quarrel. Digory wants to strike the bell, so he persuades himself that he must, that he has no choice: ‘we can’t get out of it now. We should always be wondering what would have happened… I can feel it beginning to work on me already.’ Polly disagrees: ‘You’re just putting it on’ and accuses him – tactlessly but tellingly – of looking ‘exactly like your Uncle’. Moments later their quarrel becomes physical. Digory grabs Polly’s wrist and strikes the bell. The note rises and rises ‘till all the air in that great room was throbbing with it’ and the roof falls in. They think it’s all over: ‘But they had never been more mistaken in their lives.’

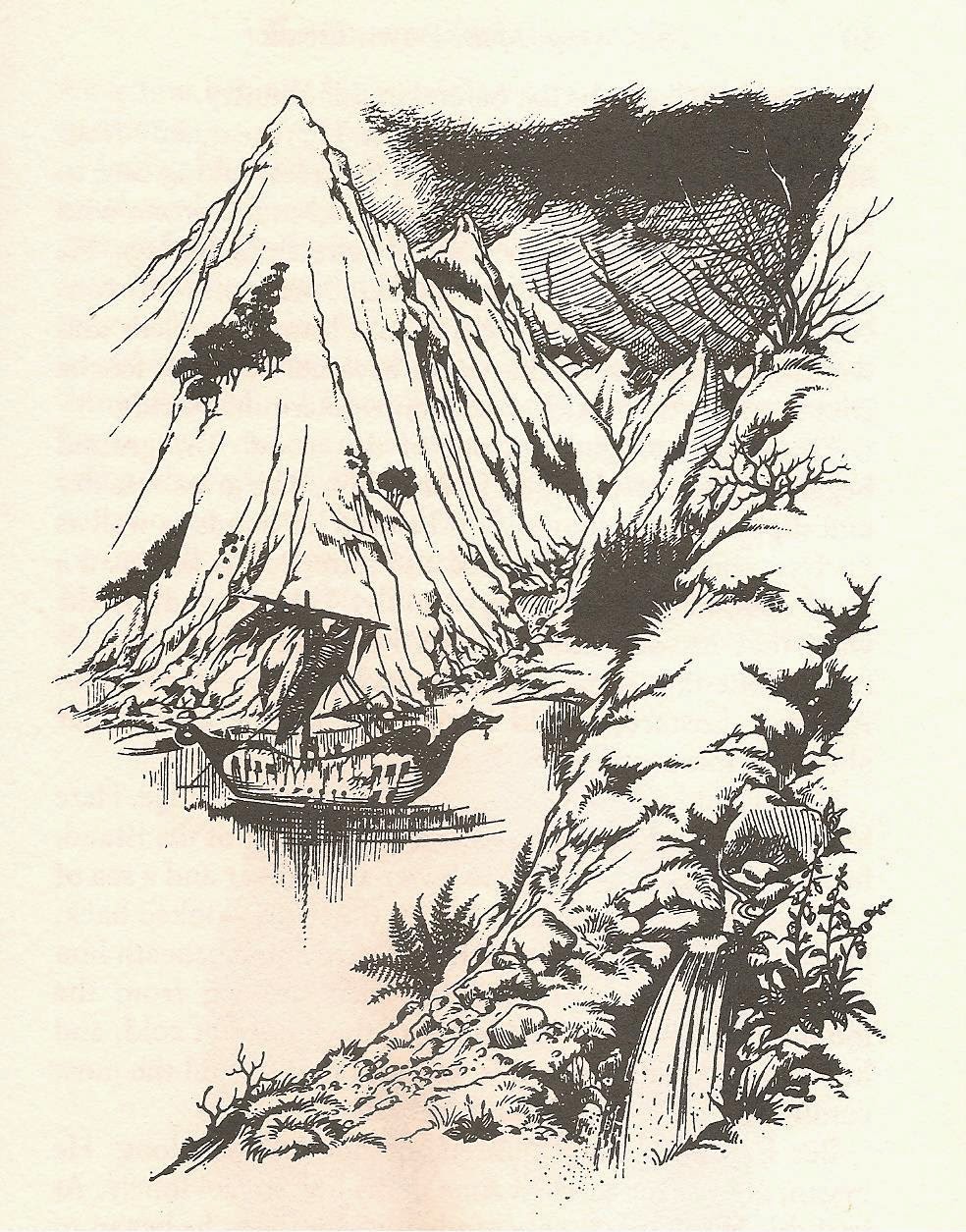

![]()

For the last Queen of Charn awakes. Tall and terrifying, she leads the children through the collapsing city. Again it’s Polly who sees Jadis most clearly for what she is, ‘a terrible woman’, ‘strong enough to break my arm with one twist’. To Digory the Queen seems ‘wonderfully brave’; he admires her as she blasts the palace doors to dust with her magic, and they emerge into the open air to see a weary red sun hanging low over the ruined horizon.

‘Look well on that which no eyes will see again,’ said the Queen. ‘Such was Charn, that great city, the city of the King of Kings, the wonder of the world, perhaps of all worlds. … All in one moment one woman blotted it out forever. …I, Jadis, the last Queen, but the Queen of the World.’

Pride, deceit, selfishness and power are the themes The Magician’s Nephew examines, and the Deplorable Word (which sounds like an enchantment out of the Morte D’Arthur) with which Queen Jadis put an end to the world of Charn, is a metaphor for the atomic bomb: towards the end of the book Aslan himself delivers a warning to the children that makes the parallel explicit. It’s not that Lewis can’t appreciate the excitement and wonder of scientific research. Here is Uncle Andrew talking marvellously about the dust in Mrs Lefay’s box, dust from another world:

‘…when I looked at that dust… and thought that every grain had once been in another world – I don’t mean another planet, you know; they’re part of our world and you could get to them if you went far enough – but a really Other World – another Nature – another universe – somewhere you would never reach even if you travelled through the space of this universe for ever and ever – a world that could be reached only by Magic – well!’

The thrill is authentic. But can the end justify the means? It depends. What are the means? What is the price of this knowledge?

‘…My earlier experiments were all failures. I tried them on guinea-pigs. Some of them only died. Some exploded like little bombs –’

‘It was a jolly cruel thing to do,’ said Digory…

‘How you do keep getting off the point!’ said Uncle Andrew. ‘That’s what the creatures were there for. I’d bought them myself.’

Perhaps it’s not so much the use of the guinea pigs here (though Lewis never spoke of vivisection without abhorrence) as Uncle Andrew’s inability to see there could even be an ethical problem. He progresses from breaking a promise, to experimenting on animals, to experimenting on Polly. For him, the guinea pigs are not living, sentient creatures but a commodity to be used – and so are the children.

Scientists don’t get a great press from Lewis. Uncle Andrew is as much scientist as magician, and the scientists Weston and Devine in Lewis’s adult trilogy Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, and That Hideous Strength are an appalling duo. But before we accuse him of simple prejudice, we should remember that in Lewis’s lifetime science had produced horrors such as mustard gas and machine guns, and in 1945, only ten years before The Magician’s Nephew was published, nuclear bombs had wiped out the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Deplorable Word is the no-first-use, last-resort weapon of Charn: even the Queen herself protests that she had no choice, had tried all other methods first. (Lewis undoubtedly has in mind Milton’s famous condemnation of Satan, who ‘with necessity,/The tyrant’s plea, excused his devilish deeds’.)

‘…I did not use my power till the last of my soldiers had fallen and the accursed woman, my sister, was … so close that we could see one another’s faces. She flashed her horrible, wicked eyes upon me and said “Victory.” “Yes,” said I. “Victory, but not yours.” Then I spoke the Deplorable Word. A moment later I was the only living thing beneath the sun.’

‘But the people?’ gasps Digory – but it’s not until Jadis echoes Uncle Andrew’s words of exculpation, ‘Ours is a high and lonely destiny,’ that he realises for the first time that even if she is ‘seven feet tall and dazzlingly beautiful’ she is as wicked as his uncle.

He is correspondingly dismayed when she announces that she intends to come with them, assuming his uncle to be a great enchanter, who

‘…for the love of my beauty has … sent you across the vast gulf between world and world to ask my favour and to bring me to him. Answer me: is that not how it was?’

‘Well, not exactly,’ said Digory.

‘Not exactly,’ shouted Polly. ‘Why, it’s absolute bosh from beginning to end.’

Why is Digory temporising? Is he tempted by Jadis’ mistake, so much more flattering to both his uncle and himself than the truth? Polly’s outburst puts an abrupt end to it. The Queen grabs her by the hair, and is drawn after the children as they vanish back to the Wood. Here the Queen can barely breathe. The children have the upper hand. They are about to jump into their own pool…

‘Help! Help! Mercy!’ cried the Witch in a faint voice, staggering after them. ‘Take me with you! You cannot mean to leave me in this horrible place. It is killing me.’

‘It’s a reason of State,’ said Polly spitefully. ‘Like when you killed all those people in your own world. Do be quick, Digory.’

Digory falters, ‘feeling a little sorry for the Queen’, and his hesitation gives the Witch the chance to seize his ear and be towed down into their own world – where Uncle Andrew is about to meet more than his match.

It’s hard not to feel that Polly is exactly right. (‘Reasons of State’: ‘Necessity, the tyrant’s plea’.) If only they had left the Witch (as she is now more and more frequently called) in the Wood, she could have done no more harm in any world. Polly is being spiteful, but doesn’t the Witch deserve it? And don’t we enjoy hearing it? What are we supposed to think?

I think Digory’s pity is tainted with admiration. Beside her fierce beauty, Uncle Andrew looks ‘a shrimp’, losing all terror. ‘Pooh,’ thought Digory to himself. ‘Him a Magician! Not much. Now she’s the real thing.’ It is a boy’s version of Uncle Andrew’s ‘dem fine woman’. If his admiration for the Witch were to continue, he might end up no better than his Uncle. Digory is in a muddle.

Polly is more clear-sighted. She quite reasonably blames first Uncle Andrew for the mess they’re in, and then Digory. ‘What have I done?’ Digory exclaims, and she makes no bones about telling him.

‘Oh, nothing of course,’ said Polly sarcastically. ‘Only nearly screwed my wrist off in that room with all the waxworks, like a cowardly bully. Only struck the bell with the hammer, like a silly idiot. Only turned back in the wood so that she had time to catch hold of you before we jumped into our own pool. That’s all.’

The surprised Digory makes a genuine apology and pleads for her help. After all, it’s his Mother he really cares about:

‘Suppose that creature went into her room. She might frighten her to death.’

‘Oh, I see,’ said Polly in rather a different voice. ‘Alright. We’ll call it Pax. I’ll come back – if I can.’ And she crawled through the little door into the tunnel.

Polly is the Hermione Grainger of Narnia.

Next comes the comic whirlwind of a chapter in which Queen Jadis wreaks havoc in the London streets. It’s closely related to Chapter 8 of E Nesbit’s The Story of the Amulet in which Nesbit’s children make desperate attempts to control and entertain an Ancient Babylonian Queen on the loose in London. Nesbit’s Queen causes chaos – she is thrown out of the British Museum as she attempts to claim her own ancient property from the glass cases – but is fundamentally well-intentioned: Nesbit even gets in a little Fabian satire.

‘…how badly you keep your slaves. How wretched and poor and neglected they seem,’ she said as the cab rattled along the Mile End Road.

‘They aren’t slaves, they’re working people,’ said Jane.

‘Of course they’re working. That’s what slaves are. Do you suppose I don’t know a slave’s face when I see it? Why don’t their masters see that they’re better fed and better clothed? Tell me in three words.’

Lewis has taken this episode and ramped it up into something far more dramatic. With Uncle Andrew as slave and lieutenant, Queen Jadis rampages through London, ambitious to be Empress of our world and hampered only by the fact that she’s lost her power of turning people to dust. The children know they must stop her, but Polly’s mother has sent her to bed in disgrace, and Digory sits alone by his window, watching anxiously for the Witch. This is when he overhears his aunt talking about his mother. ‘I’m afraid it would need fruit from the land of youth to help her now. Nothing in this world will do much.’

For Aunt Letty it’s a sentimental metaphor. But Digory ‘knew … that there really were other worlds… There might be fruit in some other world that would really cure his mother! And oh, oh…’

There must be worlds you could get to through every pool in the wood. He could hunt through them all. And then – Mother well again. Everything right again.

In Surprised by Joy, Lewis describes his own struggle with hope.

I remembered what I had been taught, that prayers offered in faith would be granted. I accordingly set myself to produce by will-power a firm belief that my prayers for her recovery would be granted; and as I thought, I achieved it. When nevertheless she died, I shifted my ground and worked myself into a belief that there was to be a miracle. … [God] was, in my mental picture of this miracle, to appear neither as Saviour nor as Judge, but merely as a magician; and when he had done what was required of him I supposed he would simply – well, go away.

I understand what he’s saying (that an interest in God generated solely by a desperate desire to have something is worthless) but compared with the poignant tenderness with which he explores Digory’s emotions, this account of himself is dry, stiff and analytical – too detached from the youthful self whose anguished efforts I find heartbreaking. Little Jack Lewis may not have loved God, but he certainly loved his mother: and so does Digory: and the love is true.

Before Digory can act on his impulse, life interrupts in the form of the Witch, splendidly and crazily standing on the roof of a hansom cab driving full tilt through the streets, pursued by a crowd of comedy Londoners delightfully unimpressed by the Empress Jadis in her splendour. The Cabby tries to calm his maddened horse, Uncle Andrew totters out of the wreckage, Jadis wrenches the cross-bar off the iron lamp-standard and fells a policeman, and Polly arrives in the nick of time. ‘Quick, Digory. This must be stopped!’ The children join hands, Digory grabs the Witch’s heel, Polly touches her yellow ring, and – with children, Witch, Cabby, horse and Uncle all stuck together like the characters in the fairytale of the Golden Goose – they rise into the Wood between the Worlds. A moment later, Strawberry the cab-horse steps into the nearest pool to have a drink, and the entire party sinks into the darkness of an unborn world.

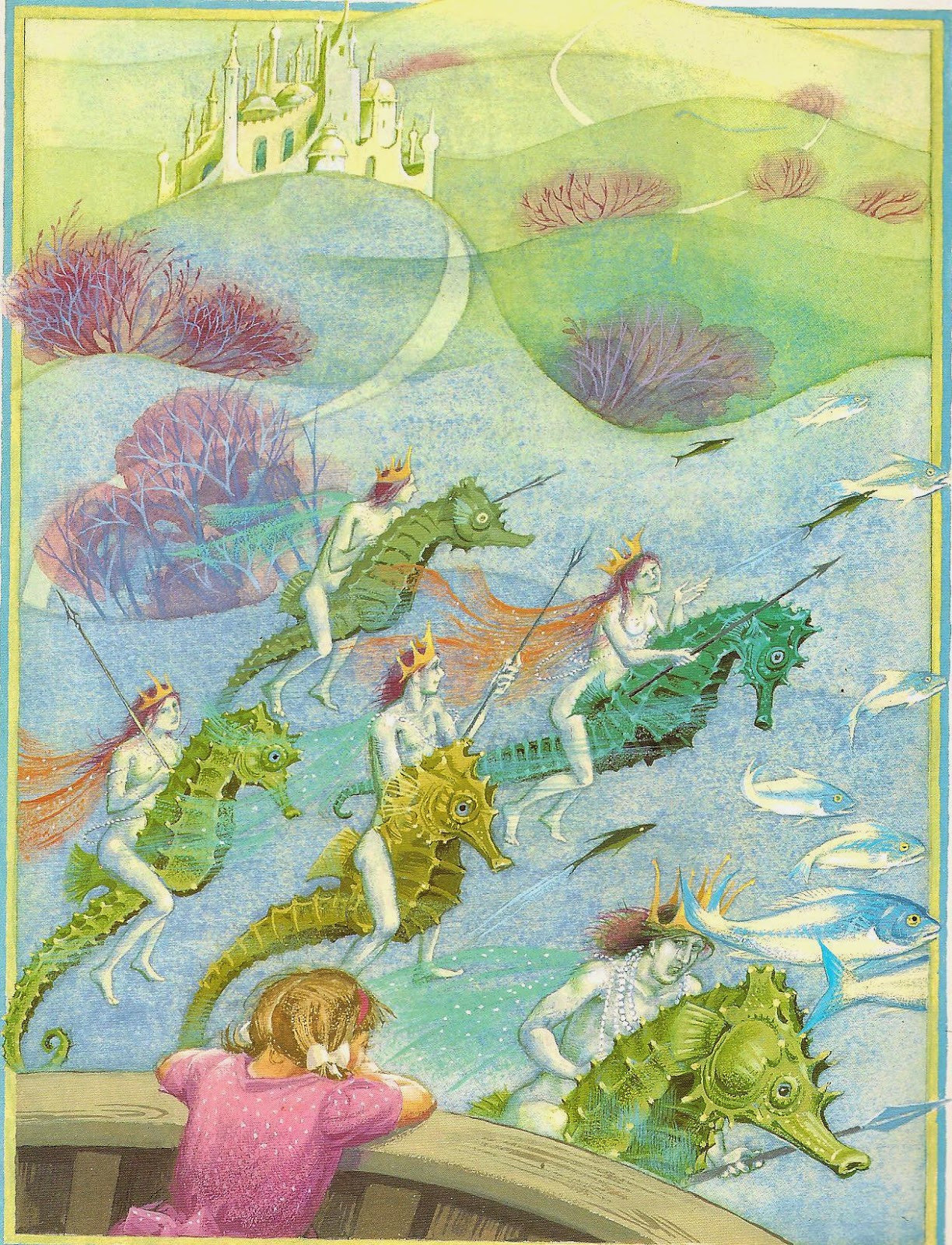

![]()

There’s an unnerving simplicity about it. ‘Under their feet there was a cool, flat something which might have been earth, and was certainly not grass or wood. The air was cold and dry and there was no wind.’

‘My doom has come upon me,’ said the Witch in a voice of horrible calmness.

In many ways, she’s right.

The Cabby takes charge – he’s not the only adult there, but he’s the only decent one – and raises spirits by singing a hymn, while Uncle Andrew sneaks and schemes – and something happens. A far-off singing begins and is suddenly joined by the voices of the stars as they spring into existence; a dawn wind springs up and the young sun rises.

You could imagine it laughed for joy as it came up. And as its beams shot across the land the travellers could see for the first time what sort of place they were in. It was a valley through which a broad, swift river wound its way, flowing eastward towards the sun … a valley of mere earth, rock and water; there was not a tree, not a bush, not a blade of grass to be seen. The earth was of many colours: they were fresh, hot and vivid. They made you feel excited; until you saw the Singer himself, and then you forgot everything else.

It was a Lion.

Each character responds individually and revealingly. The horse tears up ‘delicious mouthfuls of fresh grass’. Polly is intrigued by the correspondences between the Lion’s song and the things it creates. Digory and the Cabby are nervous, Uncle Andrew is terrified, and the Witch hurls her iron bar straight at the Lion’s head. It glances off and does no harm. She screams and runs as the Lion paces calmly past, and – enchantingly – the iron bar begins to grow into the lamp-post that will famously greet Lucy Pevensie’s eyes and give its name to Lantern Waste (it was lovely to make these connections):

…a perfect little model of a lamp-post, about three feet high but lengthening… ‘It’s alive, too – I mean, it’s lit,’ said Digory.

While Uncle Andrew’s reaction is to dream of filling Narnia with scrap metal (‘the commercial possibilities … are unbounded’), Digory realises this may truly be ‘the land of youth.’ He needs to speak to the Lion. Meanwhile the Narnian soil bubbles up with animals, and Aslan breathes consciousness into the chosen creatures: ‘Love, think, speak. Be walking trees. Be talking beasts. Be divine waters.’

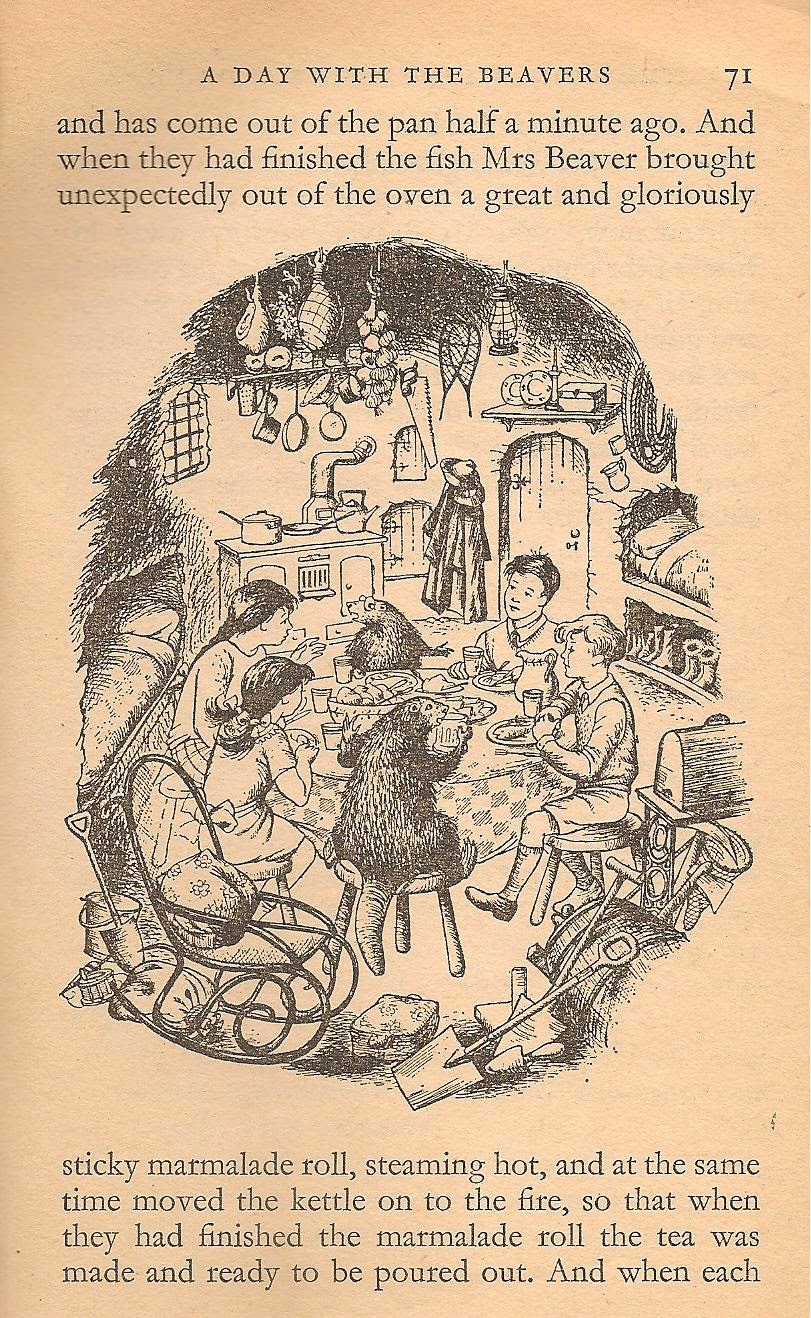

There follows a fair bit of slapstick to lighten the solemnity. I wasn’t entirely keen on this – I wasn’t a child who went for comedy much, though I can now see that most children must find it delightfully funny. The First, Second and Third Jokes left me cold, and I’m still not too sure how the Elephants fit into Narnia (in Pauline Baynes’ illustration there are even two giraffes). Perhaps they wandered off southwards. But even in the middle of all this comedy there’s a serious and characteristically clear exposition of Uncle Andrew’s thought processes: he willnot, and consequently soon cannotunderstand the Talking Beasts: ‘the trouble about trying to make yourself stupider than you are is that you very often succeed.’ Deliberate blindness is a sin to which Lewis will return in The Last Battle.

![]()

I’m afraid that the Council which Aslan calls to deal with the threat of the Witch’s presence in Narnia is, with the exception of the female raven, exclusively male – Aslan specifically names the He-Owl and the Bull-Elephant, though the She-Elephant has, arguably, a more important narrative role in planting and copiously watering the unconscious Uncle Andrew. It’s probable that Lewis did think of males as the natural councillors, but most of the real fun happens without them. And look how Digory, hoping for a cure for his mother, is brought to confess to Aslan that it’s his fault that the Witch came to Narnia. Mixed-up Digory, not Polly, is Narnia’s Eve.

‘You met the Witch?’ said Aslan in a low voice which had the threat of a growl in it.

‘She woke up,’ said Digory wretchedly. And then, turning very white, ‘I mean, I woke her. Because I wanted to know what would happen if I struck a bell. Polly didn’t want to. It wasn’t her fault. I – I fought her. … I think I was a bit enchanted by the writing under the bell.’

‘Do you?’ asked Aslan; still speaking very low and deep.

‘No,’ said Digory. ‘I see now I wasn’t. I was only pretending.’

As Digory sheds his protective layers of self-deceit, as he comes closer to honesty about himself and his motives, he gets further away from the person he might have become – his Uncle. If you’re a child reading this, you appreciate that Digory is owning up to what he did wrong – that he needs to be honest with Aslan. If you’re a Christian, you probably think in terms of confession and repentance. If you’re an atheist you may feel sickened by a deity callous enough to ignore Digory’s urgent need in order to rake over his faults. But atheists sometimes take a more literal view of God than is necessary. Unless you are a fundamentalist, God is alwaysa metaphor seen through a glass, darkly. Digory needs to be honest with himself.

Young Jack Lewis needed to be honest with himself, too. He needed to stop using magical thinking. He needed to see that it wouldn’t be his fault if his mother died: that he had no ability to save her and wasn’t responsible. ‘I think I was a bit enchanted…’ He wasn’t: he was pretending. And the pretence was an agonising waste of effort.

Digory finally understands. He can’t ‘do’ anything for his mother, but he can shoulder his real responsibilities and do the next task. That doesn’t mean an end to pain:

But when he had said ‘Yes,’ he thought of his Mother, and he thought of all the great hopes he had had, and how they were all dying away, and a lump came into his throat and tears in his eyes, and he blurted out, ‘But please, please – won’t you – can’t you give me something that will cure Mother?’

If prayer is a heart-felt plea thrown out into the universe, we all pray. The only answer we can hope for is love and a shared knowledge of grief. This, Aslan provides, and no false promises.

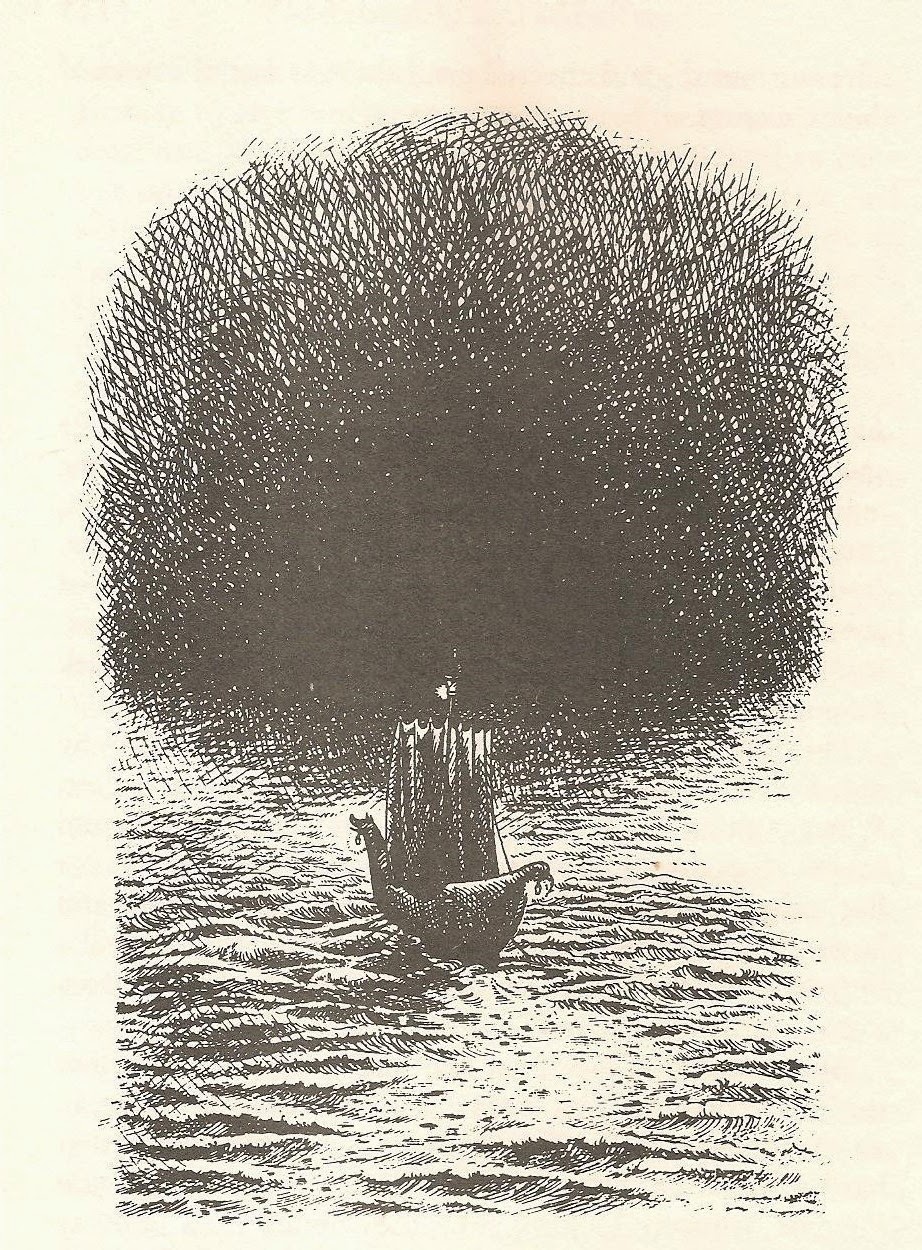

How I loved the next bit, in which Aslan turns Strawberry the cab horse into Fledge the flying horse! – a transformation enchantingly rendered by Pauline Baynes. ‘Is it good?’ asks Aslan. ‘It is very good’, Fledge responds, echoing Genesis. And off the children go on their quest to find the paradisal garden in the far West, clinging to Fledge’s back, Narnia lying fresh and unexplored below them. (‘The world only began today.’)

![]()

There are delightful and sinister episodes en route – the solution to the children’s hunger as they plant the toffees from Polly’s pocket (‘tearing the paper off the bag’) and wake next morning to find a toffee tree with soft brown fruit and whitish, papery leaves. (I love the way Lewis plays with the possibilities of the newly-created Narnia’s fruitful soil.) There’s the creepy disturbance in the night and a glimpse of a ‘tall dark figure gliding away’ – the Witch, who has overheard them talking. Now she knows the way, and when the children arrive she will already be there.

This part of the book is full of Miltonic resonances. In fact it’s fair to say that Lewis borrows his description of the tall green hill in the snowy mountains wholesale from Paradise Lost. Flying towards Eden, Satan sees Paradise, ‘an enclosure green’ crowning the head ‘of a steep wilderness’ overgrown with forest trees:

… Yet higher than their tops

The verdurous wall of Paradise up-sprung…

And higher than that wall a circling row

Of goodliest trees, loaden with fairest fruit,

Blossoms and fruits at once of golden hue,

Appeared, with gay enamelled colours mixed.

… One gate there only was, and that looked east…

Fledge descends to the green hill in the snowy mountains:

… gliding with his great wings spread out motionless on each side, and his hoofs pawing for the ground. The steep green hill was rushing towards them. A moment later he alighted on its slope … the children rolled off [and] fell without hurting themselves on the warm, fine grass…

The wall around the garden is made of ‘green turf’ (Milton’s ‘verdurous wall’): there is something about it reminiscent of a prehistoric hill fort – and is closed with high, golden gates facing east.

Inside the wall, trees were growing. Their branches hung out over the wall: their leaves showed not only green but also blue and silver when the wind stirred them.

‘You never saw a place which was so obviously private.’ Here, at the entrance to this enclosed, secret Hesperides, this paradise of apple trees, is another challenging verse in the same form as the one they found in Charn, but this time the warning is prohibitive rather than provocative.

Come in by the gold gates or not at all,

Take of my fruit for others or forbear.

For those who steal or those who climb my wall

Shall find their heart’s desire and find despair.

This time Digory gets it right, albeit with help. The gates open at a touch. The garden is full of quiet life, with a fountain and a tree loaded with ‘great silver apples’ at the centre, like Milton’s ‘Tree of Life …blooming ambrosial fruit/Of vegetable gold’.

Digory picks one for Aslan and then, tempted by the delicious smell, wonders briefly whether to pick another for himself. He considers ignoring or reinterpreting the words of warning at the gates: ‘it might have been only a piece of advice – and who cares about advice?’ Then he notices a bird, a phoenix, watching slit-eyed from the branches (Milton’s Satan sits in the Tree of Life in the form of a cormorant) but Lewis’s bird is a guard, not an intruder, in this mythical garden.

Would Digory have resisted the temptation to steal if he hadn’t seen the bird? Lewis indicates not, but leaves room for some doubt. In any case, Digory is about to be subjected to a much harder test. Half hidden in the leaves is the Witch, ‘just throwing away the core of an apple which she had eaten’ and ‘stronger and prouder than ever, and even, in a way, triumphant: but her face was deadly white, white as salt.’ She has ignored the gate and climbed over the wall like Milton’s Satan:

Due entrance he disdained, and, in contempt,

At one slight bound high overleaped all bound

Of hill or highest wall, and sheer within

Lights on his feet.

Now fully identified with Satan, she strikes hard at Digory’s weakness. The apple could save his mother, so why not take it to her at once? Where does his loyalty lie? What does he owe the Lion, a wild animal in a strange world? What would his mother think if she knew Digory could have saved her, and wouldn’t? (Was this a thought which got young Jack Lewis out of bed and on to his knees in the middle of the night?) A single mouthful would cure her. ‘Your home will be happy again. You will be like other boys.’

It is still agonising to watch Digory struggle. ‘Cruel, pitiless boy!’ the Witch reproaches. Her power is drawn from his own dark side: he turns inward, fighting his own guilt. So he made a promise? What does that matter when his motheris so much more important? He can banish her pain, give her ‘sweet, natural sleep, without drugs’. His mother would disapprove of his theft? Then don’t tell her. ‘No one in your world need know anything about this whole story.’ Finally the Witch overreaches herself. She suggests he might abandon Polly (‘You needn’t take the little girl back with you, you know’) and Digory, shocked, sees past his self-absorption. The Witch cannot be trusted.

‘Look here; where do you come into all this? Why are you so precious fond of my Mother all of a sudden? … What’s your game?’

It’s a victory, but no easy one. As the subdued children and Fledge set off eastwards with the apple, the Witch – no longer mortal – heads north to reappear, Narnian centuries later, in The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe.

Narnia is protected, meanwhile, by the great Tree which springs ‘silently, yet swiftly as a flag rises when you pull it up on a flagstaff’ from the apple in the soft soil of the riverbank. And Digory learns from Aslan that though the stolen apple would indeed have healed his mother, it would have come at a price ‘…not to your joy or hers. The day would have come when both you and she would have looked back and said it would have been better to die in that illness.’

It is strong and solemn stuff to read that there can be ‘things more terrible than losing someone you love by death’, yet it seemed to me as a child to be true, and it still does. The whole book has demonstrated by the examples of Uncle Andrew and Queen Jadis that personalities or relationships founded on deceit and selfishness are unlikely to turn out well. If there are no happy endings, there may still be a choice of unhappy ones and it may be true, as Socrates said, that it is better to suffer evil than to do it. In a way, the whole book is about how Digory ceases to be the Magician's Nephew.

‘Happy, but for so happy, ill-secured’ might be the epigraph to The Magician’s Nephew, as well as to the first chapter of Surprised By Joy. It is Satan’s comment on the precarious condition of humankind: it is Lewis’s comment on the sudden disappearance of the stability and happiness of his childhood: it is anybody’s comment who looks clear-sightedly at the world. The happy ending of The Magician’s Nephew doesn’t negate what’s happened before. Digory is not the person he would have been if his mother had never been ill.

But this is a children’s fairytale and in fairytales there is always a reward for those who triumph over adversity. Digory has fought himself and won. Now he deserves the apple Aslan gives him to take home to his mother and make her truly better.

The brightness of the Apple threw strange lights on the ceiling. Nothing else was worth looking at: indeed you couldn’t look at anything else. And the smell of the Apple of Youth was as if there was a window in the room that opened on Heaven.

‘Oh darling, how lovely,’ said Digory’s Mother.

It still makes me cry.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)