Continuing to re-post my series from 2014 on Narnia.

Much as I adored the Narnia books as a child, Prince Caspian was never my favourite among the Seven Chronicles, and the reason is as clear to me now as it was then, only then I put it differently. I found the long fifty page back-story which tells the history of Caspian and Miraz – not dull, exactly, but certainly a distraction from where I really wanted to be, which was with Lucy and Peter and Susan and Edmund in the ruins of Cair Paravel. I still read it multiple times, of course - I'd have read the Narnian telephone directory, if such a thing had existed - but I felt it wasn't as good as some of the other books.

My eight or nine-year old self was correct. Prince Caspian is clumsily constructed. The first part is the best, in which the children are called back to Narnia and gradually realise that hundreds of Narnian years have passed since they were last there. Often in writing, everything begins with an image and an emotion – a couple of things that come together like flint and iron, and strike the spark which kindles the book. I’ve got the feeling that in this book the spark of inspiration lasted Lewis through to about page 40, by which time he’d said everything he actually wanted to say. A book, however, has to be longer than that: so he had to work out a plot and people it with characters, and the story of Caspian’s childhood is reasonably entertaining, but it stops the narrative dead in its tracks for the whole middle part of the book. Then follows the children’s cross-country journey to Caspian’s aid, an unconvincing stratagem for a single combat between Peter and Miraz, a couple of treacherous Ruritanian-type lords thrown in for good measure - and Aslan at his worst: unfair, demanding and capricious. If Prince Caspian had been the only sequel to TLTW&TW, one would have to conclude that Lewis had lost his touch.

And yet it all begins so simply and so well, with the four children sitting despondently at the station waiting for the two trains which will separate them and send them away to school (‘Lucy was going to boarding school for the first time’) when –

Lucy gave a sharp little cry, like someone who has been stung by a wasp.

‘What’s up, Lu?’ said Edmund – and then suddenly broke off and made a noise like ‘Ow!’

‘What on earth –’ began Peter, and then he too suddenly changed what he had been going to say. Instead he said, ‘Susan let go! What are you doing? Where are you dragging me to?’

‘I’m not touching you,’ said Susan. ‘Someone is pulling me. Oh – oh – oh – stop it!’

Everyone noticed that all the others’ faces had gone very white.

‘I felt just the same,’ said Edmund in a breathless voice. ‘As if I were being dragged along. A most frightful pulling – ugh! it’s beginning again.’

So different is this magic summons from the easy transition through the wardrobe in the first book, I’m tempted to consider it a metaphor for the difficulty of writing a sequel. At any rate, it’s a brilliantly imagined and startling opening as the children are jerked out of England and – holding hands – find themselves ‘standing in a woody place – such a woody place that branches were sticking into them and there was hardly room to move.’

What the children (and the reader) don’t yet realise is that they’ve been called into Narnia by Caspian blowing on Queen Susan’s magic horn. How Lewis resisted the temptation to have the children actually hearthe note of a far-away faerie horn – ‘with dim cri and blowing’, as in the medieval romance Sir Orfeo - I just don’t know: but he was right. He fixes instead on the unpleasant physical sensations of being tugged, jerked, dragged out of one world into another, and unceremoniously deposited in a highly inconvenient place.

From Roland's to Boromir's, there are many wondrous horns in fantasy literature, but it seems to me that Susan’s horn is a version of the horn of Oberon in the late medieval romance ‘Huon of Bordeaux’, which Lewis knew well. In that tale (translated from the French by the Lord Berners who was Henry VIII’s Governor of Calais), the knight Huon, journeying to Jerusalem, meets the fairy king, Oberon, in a magic wood:

…the dwarf of the fairies, King Oberon, came riding by, wearing a gown so rich that it were marvel to recount… and garnished with precious stones whose clearness shone like the sun. He had a goodly bow in his hand, and his arrows after the same sort, and these had such a property that they could hit any beast in the world. Moreover, he had about his neck a rich horn, hung by two laces of gold… and whosoever heard it, if he were a hundred days journey thereof, should come at the pleasure of him that blew it.

Perhaps Susan's bow and arrows come from the same source. Characteristically inventive, Lewis shows us, not how it feels to blow such a horn, but what it’s like to be summoned by one ‘at the pleasure of him that blew it’. As the children remark, when a magician in the Arabian Nights calls up a Jinn, the Jinn has to come.

‘And now we know what it feels like for the Jinn,’ said Edmund with a chuckle. ‘Golly! It’s a bit uncomfortable to know that we can be whistled for like that.’

‘We’: original italics. Does Edmund mean ‘we public-school English children’, or ‘we kings and queens of Narnia’? In either case, the word speaks of privilege… these children have a strong sense of their own position in the world. But I like the way Lewis borrows the conventions of fairytales and medieval fantasy while turning around to look at them from the other side, so to speak: there's more of this to come.

Within a few minutes the children struggle out of the trees and find themselves

…at the edge of a wood, looking down on a sandy beach. A few yards away a very calm sea was falling on the sand with such tiny ripples that it made hardly any sound. There was no land in sight and no clouds in the sky. The sun was about where it ought to be at ten o’ clock in the morning, and the sea was a dazzling blue. They stood sniffing in the sea-smell.

‘By Jove!’ said Peter. ‘This is good enough.’

Of course: this is Narnia.

To begin with they behave like the children they are, paddling and enjoying the unexpected treat – ‘better than being in a stuffy train on the way back to Latin and French and Algebra!’ – but soon become hot, thirsty and hungry. Then they discover they are on an island, and the narrative swerves briefly into ‘shipwrecked sailor’ mode, Lewis poking a little light fun at ‘Boys’ Own’ type adventures:

Lucy wanted to go back to the sea and catch shrimps, until someone pointed out that they had no nets. Edmund said they must gather gulls’ eggs from the rocks, but when they came to think of it they couldn’t remember having seen any gulls’ eggs and wouldn’t be able to cook them if they found any. …Susan said it was a pity they had eaten the sandwiches so soon. One or two tempers very nearly got lost at this stage. Finally Edmund said,

‘Look here. There’s only one thing to be done. We must explore the wood. Hermits and knight-errants and people like that always manage to live somehow if they’re in a forest. They find roots and berries and things.’

‘What sort of roots?’ asked Susan.

‘I always thought it meant roots of trees,’ said Lucy.

At this point the children's responses are very much derived from the books they've read, but the reference to hermits and knight-errants heralds a change of tone and the discovery of the ruined castle, along with memories of the chivalric past in which the children themselves once lived. At the end of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, Lewis compressed a couple of decades of the children’s adult Narnian lives into a couple of faux-heroic pages:

Then said King Peter (for they talked in quite a different style now, having been Kings and Queens for so long), ‘Fair Consorts, let us now alight from our horses and follow this beast into the thicket, for in all my days I never hunted a nobler quarry.’

‘Sir,’ said the others, ‘even so let us do.’

In this passage it was Queen Susan who didn’t want to follow the White Stag beyond the lamp-post – ‘By my counsel we shall lightly return to our horses and follow this White Stag no further’. When I was a child I had a good deal of sympathy for her point of view: if they’d done as she suggested, they’d all have stayed in Narnia, so she was right, wasn’t she? Looking at that passage now, I see the beginning of a characterisation of Susan which continues into this book too: Susan is gallant enough, and a skilled archer, but she is also cautious, and consistently reluctant to face challenges. This isn’t about ‘being a girl’: Lucy, and in later books Jill and Polly and Aravis are evidence for Lewis’s equal treatment of the sexes. It’s just the way Susan is, and also something to do with the dynamic of keeping four main characters ‘alive’ and distinguishable from one another. In fact Peter is the most boring of the lot: he never deviates an inch from decent, fair-minded, head-boy, big-brotherhood. If Susan is practical and sharp – unfair sometimes, sometimes a bit of a nag – at least she breathes.

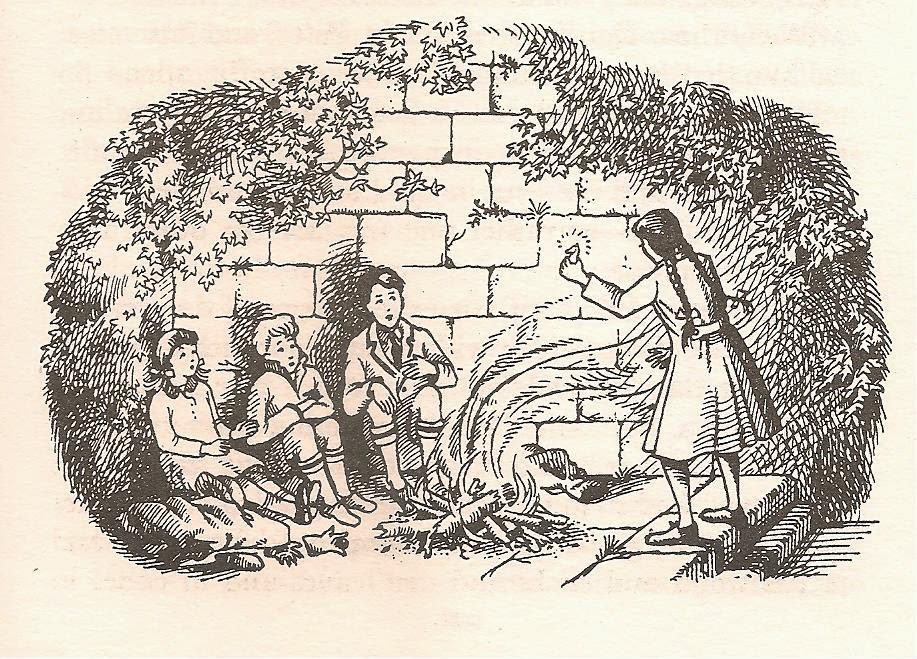

And now the children find themselves here: in an ancient apple orchard, looking at an old stone wall, and it is Susan’s turn to make discoveries. ‘This wasn’t a garden,’ she says. ‘It was a castle and this must have been its courtyard.’ And,

‘It gives me a queer feeling,’ said Lucy.

As well it might. This quiet ruin is the emotional heart of the book, and the discovery the children are about to make is – I believe – the point of the entire story; the rest is just window-dressing. It’s beautifully done. The ‘yellowish-golden’ apples on the ancient trees come with memories of the Hesperides, the secret garden, Eden – anywhere long-loved and lost. Because when the children do finally realise where they are the realisation is laden with melancholy: this is Cair Paravel, but not as it was: their Cair Paravel is gone for ever.

Still unaware, the children make camp. Susan goes to the well for a drink, and returns with something in her hand:

‘Look,’ she said in a rather choking kind of voice. ‘I found it by the well.’ She handed it to Peter and sat down. The others thought she looked and sounded as though she might be going to cry.

… ‘Well I’m – I’m jiggered,’ said Peter, and his voice also sounded queer. Then he handed it to the others. All now saw what it was – a little chess-knight, ordinary in size but extraordinarily heavy because it was made of pure gold; and the eyes in the horse’s head were two tiny little rubies – or rather one was, for the other had been knocked out.

‘Why,’ said Lucy, ‘it’s exactly like one of the golden chessmen we used to play with when we were Kings and Queens at Cair Paravel.’

In the Icelandic poem ‘The Deluding of Gylfi’, the tale is told of the end of the Norse Gods, the Aesir, at the day of Ragnarok: after which a new earth will rise out of the sea, fresh and green. Baldur will return from death, and the sons of the gods ‘will all sit down together and converse, calling to mind their hidden lore and talking about things that happened in the past… Then they will find there in the grass the golden chessmen the Aesir used to play with…’ Susan is crying because of the memories the little chess piece has brought back. ‘I can’t help it. It brought back – oh, such lovely times. And I remembered playing chess with fauns and good giants, and the mer-people singing in the sea, and my beautiful horse, and – and –’

And now Peter ‘uses his brains’ and declares that, impossible as it may seem, ‘We are in the ruins of Cair Paravel itself.’ Hundred of years must have passed in Narnia, and the four children are in the position of long-lost heroes who return to find only traces of themselves in a world which has almost forgotten them. The revelation is confirmed when they uncover the old treasury of Cair Paravel.

…and then presented the king with a small blood-hound to carry, strictly enjoining him that on no account must any of his train dismount until that dog leapt from the arms of his bearer… Within a short space Herla arrived once more at the light of the sun and at his kingdom, where he accosted an old shepherd and asked for news of his Queen, naming her. The shepherd gazed at him in astonishment and said: ‘Sir, I can hardly understand your speech, for you are a Briton and I a Saxon, but they say… that long ago, there was a Queen of that name over the very ancient Britons, who was the wife of King Herla; and he, the story says, disappeared in company with a pigmy at this very cliff, and was never seen on earth again…’

In Prince Caspian Lewis has reversed the tradition, so that while in England only a year has passed, in Narnia hundreds or maybe a thousand years have sped by. It’s as if England is a fairyland less real than Narnia. I’m sure Lewis was thinking of the story of Herla, because once the children realise what’s happened, Peter exclaims, ‘…And now we’re coming back to Narnia just as if we were Crusaders or Anglo-Saxons or Ancient Britons or someone coming back to modern England!’ ‘How excited they’ll be to see us –’ Lucy begins optimistically – and is interrupted by the sight of a boat rowed by armed men who have come to execute Trumpkin the dwarf by drowning.The book never again reaches the emotional depth of these passages, in which a children’s magical adventure story unfolds into a poignant consideration of the mysteries of loss and time. Tell me where all past things are? Where beth they beforen us weren? Ou sont les neiges d’antan? Children do ask profound questions about life, the universe and everything, and adults are frequently stumped. I remember asking my mother, ‘What would there be if there was nothing?’ and she couldn’t give a satisfactory answer. The Narnia stories were my introduction to a good many metaphysical thought-experiments. What if time is relative and runs at different speeds in different places? What if there are multiple universes? What if something could be larger on the inside than on the outside? It was exhilarating.

CS Lewis throws into the first forty pages of Prince Caspian his own experience of sehnsucht, of longing for something unattainable. Childhood? A mother’s love? Security? Peace?

Into my heart an air that kills

From yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highroads where I went

And cannot come again.

For me the rest of the book is an anti-climax. Trumpkin – or Lewis – interrupts the narrative with the history of Prince Caspian, a child version of Hamlet whose throne has been usurped by his wicked uncle Miraz, under whose alien Telmarine rule the magic of Narnia has been suppressed. It’s difficult to feel enthusiastic about Caspian – he doesn’t come alive until the next book. As a child, I tapped my foot through the story and I’m still impatient with it now - with names like Queen Prunaprismia, and academic jokes in dog-Latin aimed above children's heads, such as Caspian's grammar book written by one Pulverentulus Siccus, for goodness sake. With the help of the badger Trufflehunter, the trusty Red Dwarf Trumpkin and the untrustworthy Black Dwarf Nikabrik, Caspian escapes to lead the forces of the native Narnians, but finding his rebellion in trouble, blows on Susan’s horn for aid…

Bad Black Dwarves. I was always rather sorry for Nikabrik, bound for a bad end after trying to enrol a Hag and a Wer-wolf to Caspian’s cause. In fairytales and myths the colour black represents night and death – and by extension, evil. In the real world, I don’t need to say, the ‘white = good, black = bad’ equation has caused a great deal of trouble. Narnia isn’t the real world but a fairytale, so perhaps it’s unfair to vilify Lewis for employing the symbolism of fairytales. I merely note it’s a shame that all Black Dwarfs seem to be dodgy customers – as though hair-and-beard-colour determined your character.

Who are the usurping Telmarines? They come from a country named Telmar, beyond the Western Mountains, though it never appears on any of the maps drawn by Pauline Baynes. Prior to that they came from our human world – or Caspian would have no legitimate claim to the throne of Narnia, which by Aslan’s command must be ruled by a Son of Adam or a Daughter of Eve. This is of course a reflection of Genesis, in which Adam is given rule over the birds of the air and beasts of the field. So… how has Telmarine rule gone wrong?

‘It is… the country of the Waking Trees and Visible Naiads, of Fauns and Satyrs, of Dwarfs and Giants, of the gods and the Centaurs, of Talking Beasts. It was you Telmarines who silenced the beasts and the trees and the fountains, and who killed and drove away the Dwarfs and the Fauns, and are now trying to cover up even the memory of them,’ (says Doctor Cornelius to Caspian).

For Telmarines, read – who? What is Lewis trying to say? Who or what was it in our world which did its best to drive out belief in and cover up the memory of fauns, satyrs, the spirits of trees and fountains? The Church?The Puritans?The Education System? Is this a plea for freedom of imagination? I don’t quite know, but it seems to be a muddled if sincere claim for the vital importance of myths and stories. Or – possibly and more controversially – for belief itself. At any rate, Narnia without its magic is a poor place. When Aslan finally does turn up, he reveals himself at first only to Lucy, and there’s a reprise of TLTW&TW in which this time Edmund believes her, and Peter and Susan do not. Aslan is much less loveable, much more manipulative, in this book. He puts people to the test. He terrifies Trumpkin by seizing and shaking him – even though the children know that ‘Aslan liked the Dwarf very much.’ (And this is how to reward him?) He refuses to heal Reepicheep’s lopped-off tail until the other mice prepare to cut their own tails off in solidarity with their brave leader. You can see the difference most clearly in the bacchanal, Aslan's Romp with Bacchus and the wild girls, which so closely resembles Aslan's joyful gallop with Lucy and Susan through the springtime Narnian woods in the previous book. But what in TLTW&TW was sheer delight, culminating in the release of the Witch's stone prisoners, in Prince Caspian becomes vengeful and aggressive. Aslan frightens a group of schoolgirls and their teacher:

Miss Prizzle… clutched at her desk to steady herself and found that the desk was a rosebush. Wild people such as she had never even imagined were crowding round her. Then she saw the Lion, screamed and fled, and with her fled her class, who were mostly dumpy, prim little girls with fat legs. Gwendolen hesitated.

One is led to assume – by disassociation – that in contrast to the fat legged, dumpy girls, Gwendolen is slender and pretty. And therefore good, brave, open-minded? Guilty of fat legs or not, Gwendolen joins in Aslan’s bacchanal. This passage has not stood the test of time very well, and neither has its companion piece a page later, in which Aslan terrifies a classroom of boys who jump out of the window and are turned into pigs: shades of the Gadarene Swine? We are meant to understand that this is all right because the boys had been persecuting their young teacher whom Aslan welcomes and addresses as ‘Dear Heart’ – but the general air of ‘it serves ‘em all right’ leaves a bad taste in the mouth. Prejudices run rife. No allowances are made. There is no quarter. Finally, why have Peter and Susan, Edmund and Lucy been brought to Narnia at all? What is their narrative function? Not one of them really affects anything. Peter’s challenge to Miraz is ultimately a failure, ending in the very wholesale battle he had hoped to avert. Only Aslan’s intervention with the trees, in a scene reminiscent of the march of the Ents in The Lord of the Rings, saves the day for the native Narnians: and one assumes Aslan could have roused the trees any time he liked. Susan and Lucy literally go along for the ride. Prince Caspian seems to me to have been hastily and carelessly written, with very little of the love and attention that is evident in the first book.

There are moments. I love the scene in which Lucy almost calls the trees awake as she goes dancing through the moonlit wood. I love the descriptions of the rich loamy earth which the trees eat at the great banquet after the victory. And of course I love the first meeting with one of Narnia’s great characters, the chivalrous and martial mouse, Reepicheep. All in all, however, this is a book to be read for the sake of the first few chapters.

Things look up – a long way up – in the next title, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. But that is a post for next time.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)