I beg the indulgence of re-posting this piece about a very Christmassy book indeed. (It first appeared on this blog in 2014.) I am still busy writing my new book, which I'm hoping to finish some time in January (oh, all right then, February) - and that is why this blog has been a little neglected of late. In the meantime, I wish all of you lovely people the happiest of Christmas holidays, and all the other midwinter festivals - and the very best of new years.

Here is my much-worn, much-loved childhood copy of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

I was given my first Narnia book, The Silver Chair, when I was seven years old – a little girl living in Yorkshire in the 1960s. I went on to read the series out of sequence, ending with The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: it depended on what I could buy with my pocket money or find in the public library. The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe was published in 1950, The Last Battle in 1956, the year of my birth: so I suppose I was among the first generation of child readers of these tales.

I was given my first Narnia book, The Silver Chair, when I was seven years old – a little girl living in Yorkshire in the 1960s. I went on to read the series out of sequence, ending with The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: it depended on what I could buy with my pocket money or find in the public library. The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe was published in 1950, The Last Battle in 1956, the year of my birth: so I suppose I was among the first generation of child readers of these tales.

It’s impossible to exaggerate the effect the Narnia stories had on me. I adored them, I was super-possessive about them. I regarded Narnia as my own, private, secret kingdom – so much so that when my mother, who read aloud each night to me and my brother, suggested she might read us The Lion, The Witch & the Wardrobe, I vetoed the suggestion. Narnia was mine; I wanted to keep it all to myself. It was horribly selfish, but that was how passionate I felt. I read and reread them for years.

It’s decades now, though, since I sat down and read all of them through. Did the charm fade? I don’t know. The books were so much a part of my childhood that they still feel to be a part of me. So I’ve decided to begin again, to remind myself of what enchanted me and discover if it still has the power to do so. Over the next few months, I’ll be reading the Seven Chronicles of Narnia and letting you know my thoughts. Don’t expect academic crispness. These are likely to be long rambling posts with lots of digressions and asides as I follow wherever the fancy takes me. I hope you’ll tell me your own thoughts along the way.

So here goes: let’s talk about Narnia.

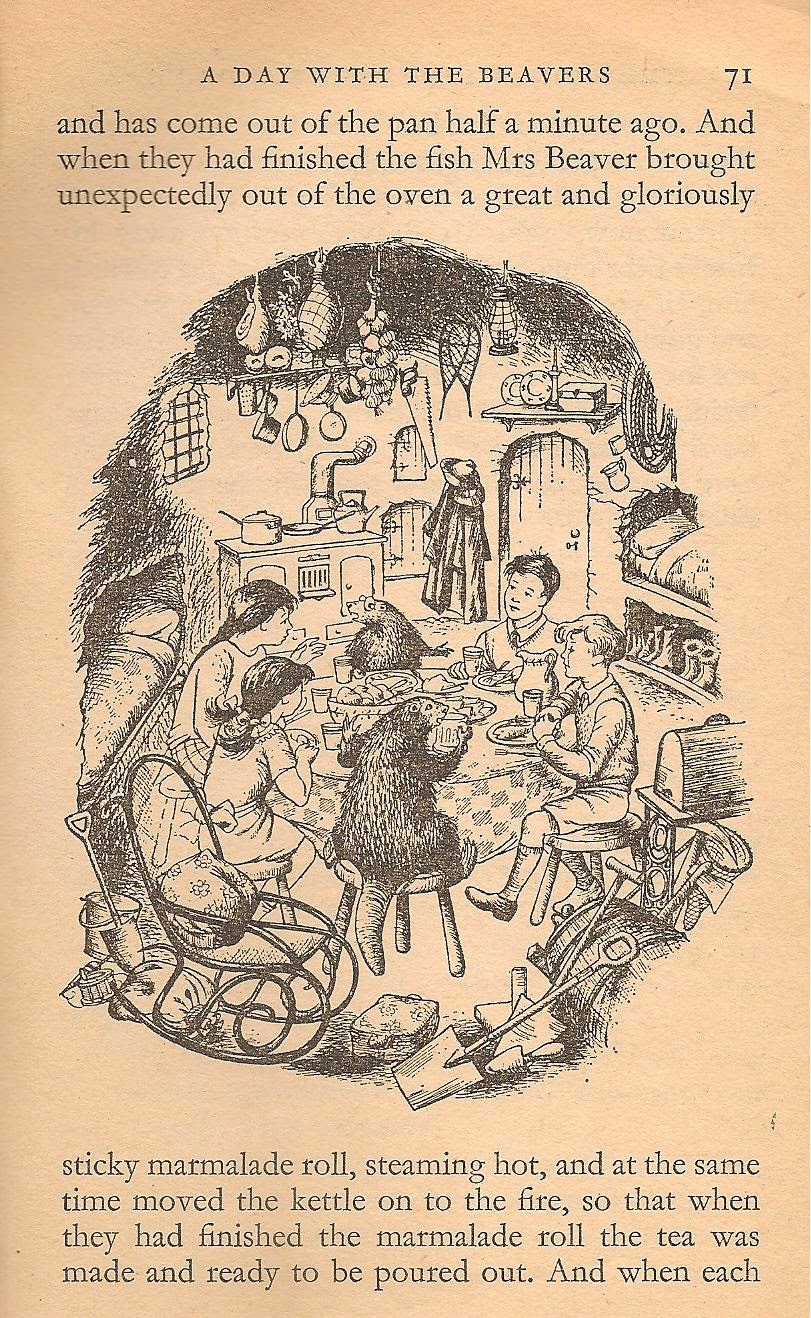

The first thing that strikes me now about The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe is how short it is: 170 pages, many with full, half, or quarter page illustrations by Pauline Baynes. I’d guess the length is not more than 35,000 words – about right for a book for seven year-olds; but books for seven year-olds written today do not commonly explore such rich emotional depths when dealing – if they deal at all – with subjects such as death, rebirth, police states, loyalty and treachery.

TLTW&TW is described by CS Lewis, in his dedication to his god-daughter Lucy Barfield, as a fairytale. Like a fairytale it deals in images, in strong, simple emotions, in primary colours, in poetic metaphor: and like a fairytale, it demands suspension of disbelief and a willingness to go along with the narrator.

Es war einmal ein König– There was once a King –

There were once four children whose names were Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy.

It doesn’t matter where or when a fairytale takes place, so Lewis disposes of the Blitz – the reason the children are sent away from London – in half a sentence. What they leave behind doesn’t matter. What matters is where they arrive: this house ‘in the heart of the country’. Which country? We aren’t told. It could be Scotland rather than England: the housekeeper has a Scottish name, and the children talk excitedly of mountains, woods, eagles and stags: but it’s the seclusion that matters. This is a secret and special place, and the further in you go, the more secret and more special it gets: inside the house there is a room, inside the room there is a wardrobe, inside the wardrobe there is Narnia…

Old houses and old castles are important places in fairytales, and there is often, too, a special hidden room. In The Twelve Dancing Princesses, the soldier must follow the princesses through an opening under the bed:

The eldest went to her bed and tapped it; whereupon it immediately sank into the earth, and one after another they descended through the opening…

and down a stair to a fabulous land where the trees have leaves of silver, gold and diamond, and where twelve princes row the princesses across a lake to a beautiful palace, to dance all night till dawn. This land is neither good nor bad (though one senses it is disapproved) but magical: other. Alternatively, as in Bluebeard or in the English folktale Mr Fox, the secret of the hidden room may be horror and death. Narnia will turn out to contain both beauty and terror.

So when Lewis chose a homely wardrobe for his doorway to Narnia (all of us had wardrobes in our bedrooms back then, before the days of fitted cupboards) he was employing a device common in fairytales, where the domestic and ordinary frequently reveal the magical and unexpected.

Here is the wardrobe – ‘the sort with looking-glass in the door’ – standing alone in an empty room. ‘Nothing there’, says Peter. But Lucy investigates. ‘This must be a simply enormous wardrobe!’ she thinks, pushing her way further in through the fur coats. And next:

Something cold and soft was falling on her. A moment later she found she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air.

A word about Lucy. Philip Pullman has accused the Narnia books of being – among other bad things – sexist, of delivering the message ‘Boys are better than girls’. People who agree with this tend, I suspect, to be thinking of ‘the problem of Susan.’ But I was a little girl reading the Narnia books, and I was never in any doubt that the main character, the clear heroine of the three titles in which she takes a prominent part, is Lucy. Any child, boys included, reading TLTW&TW will identify with Lucy for the simple reason that it’s so unfair when her siblings don’t believe her about Narnia – and even more unfair when Edmund actually lies about it. It’s as easy to identify with Lucy as it is to identify with Jane Eyre, and for the same reason: children hate injustice.

Lucy’s main-character status has always been so obvious to me, I’m puzzled why Philip Pullman has failed to spot it. Is she too gentle for him? She may not be Lyra, or even Dido Twite, but the Narnia books were written for and about children, not teenagers - and quite young children at that. Judging by the games they play and the way they squabble, Lucy, the youngest of the Pevensies, is probably about seven years old in TLTW&TW – the same age as me when I first read it. This would make Edmund eight or nine, Susan perhaps ten and Peter between eleven and twelve. Seven year olds – of whatever sex – don’t tend to be feisty, kick-ass action heroes. Lucy is sensitive, courageous, honest and steadfast, and Lewis clearly cares for her far more than he does for any of the boys. Peter and Susan are ciphers in the way older children often are in family stories of the era. Like John and Susan in Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, their main role seems to be that of surrogate parents to younger, livelier, more irresponsible siblings. Edmund is a very ordinary little boy whose silliness, jealousy and deceit are realistically sketched. Most children have occasionally behaved and felt like Edmund. But Lucy stands out. It is she who discovers Narnia, she who befriends the faun, Mr Tumnus. (And it’s Lucy and Susan, not the boys, who witness Aslan’s death and return to life: but more on the religious front later.)

Like Snow White, Lucy is quickly befriended by a denizen of the forest. And as in the seven dwarfs’ cottage, the cosy safety of Mr Tumnus’ house is soon compromised by the power of a dangerous queen. More terrifying still, Tumnus confesses himself to be a deceiver, an informer. ‘I’ve pretended to be your friend and asked you to tea, and all the time I’ve been meaning to wait till you were asleep and then go and tell Her.’ Because, and remember these books were written during the Cold War, Narnia is quite literally a police state.

‘We must go as quietly as we can,’ said Mr Tumnus. ‘The whole wood is full of her spies. Even some of the trees are on her side.’

Ashamed of himself, Tumnus is not now going to hand Lucy over to the White Witch, though this will put him at serious risk of torture and death –

‘…she’s sure to find out. And she’ll have my tail cut off, and my horns sawn off, and my beard plucked out, and she’ll wave her wand over my beautiful cloven hoofs and turn them into horrid solid hoofs like a wretched horse’s. And if she is extra and specially angry, she’ll turn me into stone and I shall be only a statue of a Faun in her horrible house until the four thrones at Cair Paravel are filled – and goodness knows when that will happen, or whether it will ever happen at all.’

This is strong stuff for young children – strong stuff for anyone. I think the reason why, in my experience at least, children aren’t very upset by it, is that they feel safe in the hands of the narrator. Lewis never forgets who he is writing for. The potential terror of Lucy’s predicament is modified by Tumnus’ repentance. The danger to her, once recognised, is already over. And for Tumnus himself, well – the danger is real enough, but this is clearly the kind of story in which good characters will, ultimately, be all right.

Children are sensitive to narrative voice, both as readers and auditors. A parent reading aloud to a child can offer reassurance at scary moments. Lewis-as-narrator offers reassurance partly by interposing himself between the child-reader and the text – commenting upon it or explaining it, thus keeping frightening or sad material at a safe distance; as in this passage from the chapter after Aslan’s death:

I hope no one who reads this book has been quite as miserable as Susan and Lucy were that night; but if you have been – if you’ve been up all night and cried till you have no more tears left in you – you will know that there comes in the end a sort of quietness. You feel as if nothing were ever going to happen again.

Is this condescension? I don’t think so. As a child, I never felt Lewis talked down to me, I felt he spoke as an equal, that he treated me seriously. He acknowledges the depth of children’s emotional experience, misery as well as happiness. By addressing the child reader directly, he turns Susan and Lucy’s grief into something we can share and understand, and the moment of Aslan’s death is thus softened and becomes more bearable.

The other method by which Lewis gently defuses fear or terror is a deft use of comedy – for example when the children and the Beavers bustle to get away from the White Witch.

‘…The moment that Edmund tells her that we’re all here she'll set out to catch us this very night, and if he’s been gone about half an hour, she’ll be here in about another twenty minutes.’

‘You’re right, Mrs Beaver,’ said her husband, ‘we must all get away from here. There’s not a moment to lose.’

The tension is both heightened and comically undercut by Mrs Beaver’s insistence on the careful and extensive packing of ham, tea, sugar, bread and handkerchieves –

‘Oh do please come on,’ said Lucy. ‘Well I’m nearly ready now,’ answered Mrs Beaver at last… ‘I suppose the sewing machine’s too heavy to bring?’

Hurry, hurry! –the child reader thinks, yet at the same time is both amused (Mrs Beaver is being funny) and reassured (Mrs Beaver is a mother figure, and if she’s not scared, neither need we be).

If Lewis were not so skilful, this could and would be a deeply unsettling book. There’s Edmund’s treachery – to his own brother and sisters, no less. There’s the scene of the Faun’s cosy house in ruins –

The door had been wrenched off its hinges and broken to bits. …Snow had drifted in from the doorway and was mixed with something black, which turned out to be the charred sticks and ashes from the fire. Someone had apparently flung it about the room and then stamped it out. The crockery lay smashed on the floor and the picture of the Faun’s father had been slashed to shreds with a knife.

It’s no small achievement to be this frank, this clear about spite and violence and hate – confirmed by the denunciation on the door signed ‘MAUGRIM, Captain of the Secret Police’ – in a book for small children which most of us remember as full of magic and delight. There’s the threat to Edmund himself from the White Witch, who is ready to murder him. There’s the truly upsetting scene when the Witch turns to stone a happy little party of fauns and animals, for the crime of telling the truth. (This is also the moment at which Edmund feels compassion for the first time.)

‘What is the meaning of all this gluttony, this waste, this self-indulgence? Where did you get these things?’

‘Please, your Majesty,’ said the Fox, ‘we were given them …’

‘Who gave them to you?’ said the Witch.

‘F-F-F-Father Christmas,’ stammered the Fox.

‘What?’ roared the Witch… ‘…How dare you – but no. Say you have been lying and you shall even now be forgiven.’

At that moment, one of the young squirrels lost its head completely.

All this, before we’ve even got to the death of Aslan.

As is well known, JRR Tolkien didn’t get on with Narnia, and one of the things that annoyed him about the series was Lewis’s carefree – or slapdash, depending on your viewpoint – world-building, bundling together everything and anything he’d ever loved in myth, legend and fairytales. Thus Narnia has not only talking animals out of Beatrix Potter or The Wind in the Willows, it also has nymphs, naiads, dryads and river gods from classical mythology, and giants and dwarfs out of the Northern legends. It borrows Green Ladies from medieval romances, and mystical islands from Celtic voyage tales and, in this one first book, it has Father Christmas.

But when a writer has come up with a lovely phrase like ‘Always winter and never Christmas’, well what is he to do? I don’t mind this single meeting with Father Christmas in Narnia, although I do think Lewis was wise not to invite him back. He seems to me to echo the appearance of Grandfather Frost in Russian fairytales – the white-bearded old spirit of the snowy woods who just may, if you address him politely, give you gifts (rather than freezing you to death). Personally I find Father Christmas in Narnia easier to accept than Tolkien’s facetious reference to golf in The Hobbit, when Bilbo’s ancestor Bullroarer Took knocks off the head of the goblin king Golfimbul. ‘It sailed a hundred yards through the air and went down a rabbit hole, and in this way the battle was won and the game of golf invented at the same moment.’ Such self-conscious flippancy was one of the things that put me off The Hobbit as a child.

And now for the vexed question of religion.

People talk a lot nowadays about the Narnia stories as religious allegories. They really aren’t. Lewis wrote a textbook about medieval allegory – ‘The Allegory of Love’ – and knew what it was and what it wasn’t. There is Christian symbolism in the books, but that is not at all the same thing. And it went clean over my head as a child. Aged about ten, I remember saying shyly to my mother that ‘it almost feels as if Narnia is real’. (What I actually wanted to say was ‘I believe Narnia is real’ – because the alternative, that Narnia had no existence except between the pages of a book– was almost unbearable.) My mother didn’t spoil the book for me by telling me that Aslan is meant to be Christ. She just replied quietly, ‘I think you’re meant to feel that.’ And so the religious message in the books remained invisible to me – at least until The Last Battle more or less rubbed my face in it. Indeed, talking to some teenage Muslim girls a year or two ago, I got surprised looks when I mentioned the Christian elements in the Narnia stories. They hadn’t noticed, either. There is a difference, I think, between the ways in which children and adults read. Children are more immersed in a book – more trusting, more literal. They take what they read at face value. They don’t come up for air and think, as adults do, ‘Just what is this author trying to say?’

Does this make children potentially more vulnerable to prejudice and propaganda? Perhaps. But it’s interesting to look at a much more obvious attempt at Christian fantasy by the Catholic children’s author Meriol Trevor, written a decade after the Narnia books, in 1966. In The King of the Castle (Macmillan), a sick boy, Thomas, finds his way into the world of a picture hanging on his bedroom wall and meets Lucius, a shepherd with a phoenix ring, who believes himself to be the son of the High King. Reviled, disbelieved, eventually hanged, Lucius is restored to life by a Messenger of the High King, and claims his kingdom. The Christian message was obvious to me when I read the story as a child, but it didn’t capture my imagination, and a recent re-reading showed why: Lucius is wooden, the resurrection scene almost perfunctory, and there seems no narrative reason why the viewpoint character Thomas should be in this world at all. The book has nothing of the verve, the colour, the energy of the Narnia stories.

Philip Pullman speaks for many who consider the Narnia books outrageous propaganda for the pernicious doctrine of an all-powerful God who demands innocent blood to atone for the sins of a supposedly corrupt humanity. From this viewpoint TLTW&TW is dodgy stuff. For a Christian reader, however, such a view is a travesty of the New Testamant stories and the doctrine that declares Christ to be a facet of a living and loving God who shares in the suffering of the world. No one, least of all myself, is going to be able to reconcile such opposite perceptions.

But remember CS Lewis called his book a fairytale, and in fairytales the world over, good and innocent characters who die, come back to life. Think of Snow White in her glass coffin! In The Juniper Tree, the murdered boy is transformed into a beautiful, mysterious bird which deals out justice, rewarding the good and destroying the wicked, before turning back into a living child again. In Fitcher’s Bird, the third bride is able to restore her murdered sisters to life and escape the house of the sorcerer. Resurrections occur in fairytales because here, if nowhere else, there is a real chance that justice and goodness may prevail over evil and tragedy. Lewis came to Christianity through stories: he took them seriously: he regarded the incarnation, death and resurrection of Christ as a fairytale which really happened. We don’t have to follow him all the way. But we can still be moved by the tales.

It is perfectly natural for a child to read The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe and to see Aslan as no more and no less than the literal account makes him: a wonderful, golden-maned, heroic Animal. I know, because that’s the way I read it, and that is why I loved him. Though the death of Aslan at the hands of the White Witch is the heart of the book, that ‘deep magic from the dawn of time’ works just as well on a non-Christian level. A beautiful, icy queen: a golden lion. ‘When he shakes his mane, we shall have spring again…’ Of course Aslan comes back to life! Who can kill summer?

My childhood copy of the map of Narnia...

Picture credits

All artwork by Pauline Baynes. The full colour illustration of Lucy and Mr Tumnus is from Brian Sibley's 'The Land of Narnia', Collins Lions, 1989

Picture credits

All artwork by Pauline Baynes. The full colour illustration of Lucy and Mr Tumnus is from Brian Sibley's 'The Land of Narnia', Collins Lions, 1989