This is the text of an address I gave at the Adderbury Literary Festival on Friday November 22nd, to mark the 50th anniversary of CS Lewis's death.

When I was a little girl living near Ilkley in Yorkshire, an exciting rumour ran around my primary school. A famous author was coming to live nearby! But when we heard who it was, my friends and I were rather disappointed. It was only Enid Blyton – and even though we’d all read masses of Enid Blyton’s books, and the news was interesting, we couldn’t help wishing it had been someone different. We couldn’t help wishing it could have been CS Lewis. We didn’t realise it was already too late for that. He had died on the 22nd of November 1963.

It’s hard to believe fifty years have passed since CS Lewis's death. But his books live on. The Seven Chronicles of Narnia are among the best-selling children’s books in the world; they have sold over 100 million copies worldwide and been translated into 47 languages; they’ve been broadcast on radio at least twice, they’ve been made into a BBC TV series, they’ve been turned into films and even videogames. Not bad for seven children’s books written by a middle-aged Oxford professor between 1949 and 1954.

It’s impossible to exaggerate the effect that the Narnia books had on me when I discovered them as a child. I adored them. I was super-possessive about them. I regarded Narnia as my own, private, secret kingdom – so much so that when my mother, who read aloud to us every night, suggested she might read The Lion, The Witch & the Wardrobe to me and my brother, I made such a fuss about it that she gave in. I didn’t want my brother to get into Narnia. I wanted to have it all to myself! I was in fact quite horribly selfish about it, and I shudder to think what Aslan would have had to say, but that was how passionate I felt.

Because you see, it was myNarnia. Even though the Narnia books have been read by so many people, each and every child who picks up a copy of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and begins to read it, gets into Narnia by themselves. In spite of all those millions of readers, it’s not a crowded place. If I could have understood that, perhaps I would have realised that sharing Narnia with my brother wouldn’t make any difference to the magic.

Well, at least here, tonight, I can make up for my selfishness a little – by sharing Narnia with all of you.

I’d like to talk first about my own experience of discovering Narnia, and then a bit more broadly about some of the sources CS Lewis drew upon and about some of the stories behind the books. Finally, the Narnia stories have become controversial in recent years. They’ve been criticized by several modern commentators, notably Philip Pullman, for what is regarded as Christian propaganda, racism, and misogyny – accusations that would have made me burn with indignation as a child, if I could have understood them. Whether I now agree with them or not, there is a case to be answered and I will try my best to do so.

The first time I ever saw one of the Narnia books was one Christmas Day when I was about seven or eight years old. My mother had bought it for me as a Christmas present, along with about six other books (all I ever wanted was books). It was The Silver Chair, and I didn’t like the look of it.

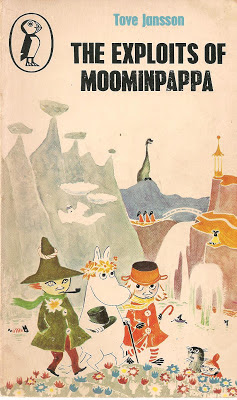

The cover picture, one of Pauline Baynes marvellous illustrations, shows a gloomy-looking cavern with lots of grotesque little gnomes, and I’m sorry to say it put me right off. I had no idea what the book might be about; I had never heard of Narnia or CS Lewis, but this looked downright sinister to me, and it reminded me of Gollum, in The Hobbit, which had given me the creeps – and, worse still, of a truly ghastly Grimms’ fairytale ‘The Hobyahs’.

So I put off reading it as long as I could. I read all my new Enid Blyton books, and – I seem to remember – Elizabeth Goudge’s The Little White Horse, and then I was stuck with nothing new to read but this one, and as I was the sort of child who would read the back of cornflakes packets if there was nothing better to hand, I rather reluctantly opened it and began. And it started quite manageably, after all:

It was a dull autumn day and Jill Pole was crying behind the gym.

It seemed a school story. But almost immediately, the narrator went on to say, ‘This not going to be a school story’ – and then Eustace Scrubb comes along and tells Jill there’s this chance of escaping the bullies of Experiment House by getting ‘right outside this world’ – and then, ah then, in almost no time, Jill and Eustace find themselves on a high mountain – at the top of a cliff.

Imagine yourself at the top of the very highest cliff you know. And imagine yourself looking down to the very bottom. And then imagine that the precipice goes on below that, as far again, ten times as far, twenty times as far. And when you’ve looked down all that distance, imagine little white things that might at first glance be mistaken for sheep, but presently you realise they are clouds – not little wreaths of mist but the enormous white, puffy clouds that are themselves the size of mountains. And at last, in between those clouds, you get your first glimpse of the real bottom, so far away that you can’t make out whether it’s field or wood, or land or water: further below those clouds than you are above them.

Well,Jill shows off and Eustace falls over the cliff – and a lion appears and blows them both to Narnia ‘blowing out as steadily as a vacuum cleaner sucks in’ –

And there I was in this adventure, full of old castles and dying kings, forlorn hopes and bright colours, and snowy moors and talking owls, and Puddleglum the Marshwiggle, gloomy but brave – and the beautiful belle-dame–sans-merci-type Green Witch – and those gnomes who seemed so sinister turned out to be just fine in the end – with time running out to save Prince Rilian from that terrible, magical engine of sorcery, the Silver Chair itself.

And I was hooked. It was about the best story I’d ever read. More than that: there was more to itthan any story I’d ever read. After all, there was such a lot to think about. It was Lewis, not any scientist, who introduced me to the concept of the multiverse – the idea there could be many worlds, many universes besides ours. He also introduced me – little as I realised this at the time – to the Platonic parable of the cave. Just as much as Christianity, the ancient Greek philosopher Plato was one of CS Lewis’s touchstones: he even gets a mention in The Last Battle: “It’s all in Plato – all in Plato,” says the Professor, Diggory. “Bless me, what do they teach them in these schools?” In The Republic, Plato suggests that human lives can be compared to the lives of prisoners chained up in a cave, whose only knowledge of the reality which lies outside is gained from the shadows flung on to the cave wall from the world beyond. That is what lies behind this passage, in which the Green Lady, the witch, is trying to persuade the children and the Prince that there is no such place as Narnia:

“What is this sun that you speak of? Do you mean anything by the word?”

“Yes, we jolly well do,” said Scrubb.

“Can you tell me what it’s like?” asked the Witch (thrum, thrum, thrum, went the strings).

“Please it your Grace,” said the Prince, very coldly and politely. “You see that lamp. It is round and yellow and gives light to the whole room; and hangeth moreover from the roof. Now that thing which we call the sun is like the lamp, only far greater and brighter. It giveth light to the whole Overworld, and hangeth in the sky.”

“Hangeth from what, my lord?” asked the Witch, and then, while they were all still thinking how to answer her, she added, with another of her soft, silvery laughs, “You see? When you try to think out clearly what this sunmust be, you cannot tell me. You can only tell me that it is like the lamp. Your sun is a dream; and there is nothing in that dream that was not copied from the lamp. The lamp is the real thing; the sun is but a tale, a children’s story.”

Some might call this a bit of Christian propaganda. And it certainly can be interpreted that way: but first and foremost it is a neat reversal of Plato’s image. Here it’s the Green Lady who inhabits – mentally as well as literally – the underground cave. She wants to restrict the children’s reality. She wants to keep them with her, prisoners – just as the dwarfs at the end of The Last Battle are prisoners of their own scepticism, refusing to emerge from the rank stable of their own senses. What is real? Lewis asks. Is it only the evidence of our immediate senses – what we can touch and taste and see? Then what about the imagination? What about poetry and religion and philosophy?

But the children know Narnia is real, and Lewis hints at how impoverished the witch’s worldview is by showing us layer upon layer of rich reality: the glimpse of the brilliant land of Bism far down in the depths of the earth:

“Down there,” said Golg, “I could show you real gold, real silver, real diamonds.”

“Bosh,” said Jill rudely. “As if we didn’t know that we’re below the deepest mines even here.”

“Yes,” said Golg. “I have heard of those little scratches in the crust that you Topdwellers call mines. But that’s where you get dead gold, dead silver, dead gems. Down in Bism we have them alive and growing. There I’ll pick you bunches of rubies that you can eat, and squeeze you a cup full of diamond juice. You won’t care much about fingering the cold dead treasures of your shallow mines after you have tasted the live ones of Bism.

What is real? Our world? Fiction? Narnia? Aslan’s country? All of them…?

With such questions hanging in the Narnian air, no wonder that I, along with many other children, felt a passionate half-belief that Narnia was real. And we longed to go there. The American writer Laura Miller writes of this in her wonderful ‘The Magician’s Book, A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia’:

In one of the most vivid memories from my childhood, nothing happens. On a clear, sunny day, I’m standing near a curb in the quiet suburban California neighbourhood where my family lived, and I’m wishing, with every bit of myself, for two things. First, I want a place I’ve read about in a book to really exist, and second, I want to be able to go there. I want this so much I’m pretty sure the misery of not getting it will kill me. For the rest of my life, I will never want anything quite so much again. The place I longed to visit was Narnia.

I understand that so well. When my friend Frances and I were about ten, we confessed to one another our fragile belief that Narnia was real – had to be real. We invented a code name for it – ‘The Garden’ – so that we could talk about it and other people wouldn’t know. (That jealous secrecy again!) And I remember shyly telling my mother that I ‘almost felt as though Narnia is real’. “I think you’re supposed to,” was all she said, and did not elaborate. I’ve always been grateful.

Enchanted and swept away, I read all the other books as fast as I could, gobbling them up in random order one after another as they were given to me for birthday or Christmas presents, or borrowed from the library. The order you read them in didn’t really seem to matter. The day I finished the series with ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’ was a memorable day for me. My little brother was in hospital recovering from an emergency operation, and my parents knew that a present of the book I’d been longing for would keep me happily tucked up in an armchair for a couple of hours while they went visiting. I can still almost feel the chair’s bristly upholstery against my bare legs as, quite unconcerned about my poor little brother, I curled up and began to read.

‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’ swept me away into an open-air world full of light. Light pervades the book: the light of sunrise over the sea, the sunlit quiet passages of the Magician’s House, sunbeams penetrating the green waters of the undersea world beneath the ship, the birds that come flying out of the rising sun to the table of the Three Sleepers, the almost painful light of the Silver Sea.

...when they returned aft to the cabin and supper, and saw the whole western sky lit up with an immense crimson sunset, and thought of unknown lands on the Eastern rim of the world, Lucy felt that she was almost too happy to speak.

For me, age ten, the island-hopping voyage of Caspian and his friends to the End of the World seemed completely original, but I now know that, as authors do, C.S. Lewis was borrowing. (We all do this all the time, by the way.) You only have to stop for a second to see how much the White Witch in The Lion the Witch & the Wardrobe owes to Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen: the tall, icy queen, the sledge, the reindeer, and the little boy whom she seduces and steals away. I can also now see the parallels between ‘The Silver Chair’ and the medieval English poem ‘Gawain and the Green Knight’ – especially the snowy winter journey over rough countryside, and the supernatural Green Lady who echoes the Green Knight of the early poem.

CS Lewis was of course immensely well-read, a medieval scholar to his fingertips, and you could say he raided his store–cupboard of magical delights and passed them on to children. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader echoes some very old Irish voyage tales known as immrama, in which a hero or saintsset out for some kind of Otherworld, stopping at a number of fantastic or miraculous islands along the way. Written in the Christian era, they hark back to older pre-Christian Celtic voyage tales, and may also have been consciously influenced by the classical tales of the Odyssey and Argonautika.

In ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’, King Caspian and his friends are hoping to find ‘Aslan’s own country’: just as the Irish St Brendan sets out to find the coast of Paradise. And they succeed, in spite of Lucy’s question, ‘But do you think… Aslan’s country would be that sort of country – I mean, the sort you could ever sailto?’

The answer of the immrama is always: ‘Yes! Although you may not always get back.’ The hero Bran set out in his skin boat or curragh to search for the wondrous Isle of Women where no one is ever sick or dies.

On arrival, Bran’s boat is drawn into port by a ball of magical thread which the queen of the island tosses to him. The sailors remain there happily, unaware of how much time is passing in the real world, until homesick Bran decides to return home. The queen warns against it, and especially against setting foot on land, but Bran insists – but when they reach Ireland, so many years have passed that Bran’s name is only an ancient legend, and when one man leaps out of the curragh, he crumbles to dust. Seeing this, Bran and his companions sail away, never to be seen in Ireland again.

In just the same way, the heroic Talking Mouse Reepicheep sails over the edge of the world in his coracle, “and since that moment no one can truly claim to have seen Reepicheep the Mouse. But my belief is that he came safe to Aslan’s country and is alive there to this day.”

The islands in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader– the dragon island, the Dark Island where dreams come true, the Island of the Dufflepuds, the island of The Three Sleepers – these are deliberate echoes of those the Irish hero Maeldune visits: thirty or so marvellous islands and a variety of other wonders, including the Isle of Ants – ‘every one of them the size of a foal’; the Island of Birds; an island where demon riders run a giant horse race; an island of a miraculous apple tree whose fruit satisfy the whole crew for ‘forty nights’; an island of fiery pigs, an island of a little cat; an island where giant smiths strike away on anvils and hurl a huge lump of red-hot iron after the boat (surely a volcanic eruption?) so that ‘the whole of the sea boiled up’.

Here’s an excerpt from The Voyage of Maeldune:

The Very Clear Sea

They went on after that till they came to a sea that was like glass, and so clear it was that the gravel and the sand of the sea could be seen through it, and they saw no beasts or monsters at all among the rocks, but only the clean gravel and the grey sand. And through a great part of the day they were going over that sea, and it is very grand it was and beautiful.

Surely this influenced C.S. Lewis’s ‘Silver Sea’! ('How beautifully clear the water is' said Lucy to herself as she leaned over the port side early in the afternoon...'I must be seeing the bottom of the sea; fathoms and fathoms down.'

Having gobbled up the last of the Narnia books, I was so desperate to read another one that I began writing my own. It was the next best thing to getting there. “Tales of Narnia”, I called it, and filled an old hardbacked exercise book with stories and pictures based on hints Lewis had left in the Seven Chronicles: “The Story of King Gale”, “Queen Camillo”, “The Seven Brothers of Shuddering Wood”, “The Lapsed Bear of Stormness”.This was the beginning of my life an author. For one thing, it taught me the difference between reading and writing. I think I began these stories hoping to re-renter Narnia, but I found that as a creator, my own work hardly satisfied me. Guess what? I couldn’t write as well as CS Lewis! It was the beginning of a long journey.

![]()

And I copied out Pauline Baynes’ map of Narnia in loving detail. There it all was, as if looking down from an eagle’s eyrie: the indented east coast with Glasswater Creek and Cair Paravel; Archenland to the south; Dancing Lawn and Aslan’s Howe and Lantern Waste in the centre of the map; Harfang and Ettinsmoor to the north.

Looked at in realistic terms, I suppose the map is really pretty sparse, but it didn’t matter. Narnia isn’t the sort of fantasy world in which one worries about economics, transport, coinage, or supply and demand. In fact, as soon as any of the characters start thinking in those terms themselves (King Miraz, for example, or the governor of the Lone Islands) they get into trouble. (“We call it ‘going bad’ in Narnia,” as Caspian magnificently remarks.) Narnia self-corrects in that respect: it will allow the existence of a Witch Queen who rules over a century of winter, but it will not permit the existence of taxation and compulsory schooling.

This can hardly be because Lewis disapproved of taxation and compulsory schooling. It’s because Narnia is a child’s world, and no ideal world for children is going to include anything so dull.

People talk a lot nowadays about the Narnia stories as religious allegories. They really aren’t. There is Christian symbolism in the books, but that is not at all the same thing. And it went clean over my head as a child. It was invisible to me – at least until The Last Battle more or less rubbed my face in it. And then I did my excellent best to forget about it. Indeed, talking to some teenage Muslim girls a year or two ago, I got surprised looks when I mentioned the Christian elements in the Narnia stories. They hadn’t noticed them either; I had to explain why, how Aslan is a parallel to Christ. I think Lewis, who only came to Christianity through stories, actually minded far more about the story than the allegory.

It is perfectly natural for a child to read “The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe” and to see Aslan as no more and no less than the literal account makes him: a wonderful, golden-maned, heroic Animal. I know, because that’s the way I read it, and that is why I loved him. Though the death of Aslan at the hands of the White Witch is the heart of the book, that ‘deep magic from the dawn of time’ works just as well on a simpler non-Christian level. A beautiful, icy queen: a golden lion. “When he shakes his mane, we shall have spring again…” Of course Aslan comes back to life! Who can kill summer?

As for “The Last Battle”, in which the Christian parallels become more explicit, it is far less popular with children, because everything goes wrong, and Narnia ceases to be, and Aslan turns into Someone Else: “And as He spoke, He no longer seemed to them like a lion...” What? What? I didn’t want the new heaven and the new earth and the new, improved Narnia, thank you very much. I wanted the old one, and Aslan the Lion, and things to go on as they always had.

So what – if anything – is wrong with Narnia? The writer Philip Pullman is not alone in disliking the books – and Lewis – intensely. For example, what about the wholesale deaths of all the child characters in an unseen railway accident at the end of The Last Battle:

“To solve a narrative problem by killing one of your characters is something many authors have done,” Pullman remarks in a 1998 article for The Guardian entitled ‘The Dark Side of Narnia’. “To slaughter the lot of them, and then claim they’re better off, is not honest storytelling: it’s propaganda in the service of a life-hating ideology. But that’s par for the course. Death is better than life, boys are better than girls, light-coloured people are better than dark-coloured people; and so on. There is no shortage of such nauseating drivel in Narnia, if you can face it.”

These are serious accusations which deserve serious consideration. The first, that Lewis feels ‘death is better than life,’ I feel is an over-statement, although I agree that The Last Battle is a difficult and flawed book. Philip Pullman is quite right to complain about sleight-of-hand. Lewis glosses over the railway accident deaths to the point of artistic dishonesty. It’s not shown. There’s no pain, no suffering, no horror. Lewis should have known better: he did know better. The death of Aslan in The Lion the Witch & the Wardrobe is tremendously moving, because it is taken seriously. The railway accident in The Last Battle is an invisible afterthought with no emotional credibility. The children don’t even know they’ve died. And I never believed in any of it for a moment.

So: one strike against him. But I don’t agree that Lewis was saying that ‘death is better than life’. The whole point of The Last Battle is that death is a doorway to more life. However, he didn’t succeed in convincing this child that anywhere could be better than the old Narnia.

‘Boys are better than girls’. Here we’re on firmer ground. I’m sorry, Mr Pullman, but this is twaddle. People who say this tend, I suspect, to be thinking of ‘the problem of Susan.’ But I was a little girl reading the Narnia books, and I knew for certain that the main character, the undoubted heroine of the first three books, is Lucy. She’s courageous, honest and steadfast – and Lewis quite obviously cares far more for her than he does for any of the boys. Peter and Susan are ciphers in the way that older children often are in family stories of that era. Like John and Susan in Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, their main role seems to be that of surrogate parents to their younger siblings. But Lucy stands out. Lucy discovers Narnia. Lucy befriends the faun, Mr Tumnus. Lucy and Susan, not the boys, are the witnesses to Aslan’s death and resurrection. In Prince Caspian, Lucy is the one who can see Aslan when no one else can. In The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, it’s through Lucy’s eyes that we see the nightmare terrors of the Dark Island as they threaten to overwhelm the crew: it’s Lucy who sees the light in the darkness, it’s Lucy who climbs the stairs and walks down the silent corridor to the Magician’s chamber. Lucy shines.

And in The Silver Chair, it’s Jill Pole, not Eustace, who is the viewpoint character. We see Narnia through her eyes, and she has common sense, courage and obstinacy. Yes, she pushes Eustace off a cliff – but anyone might do that. She and Eustace are quite definitely equal partners. It’s Jill who discovers that the giants of Harfang mean to eat the children and the Marshwiggle for the Autumn Feast – and in The Last Battle, Jill is an actual combatant, who stands alone in front of King Tirian’s small group of supporters to shoot her arrows at the Calormene army. Even the female villains in Narnia have incomparably more energy, style and flair for wickedness than the male ones do. Compare Queen Jadis, driving the hackney carriage like Boadicea in her chariot, with creepy, snivelling Uncle Andrew; compare the White Witch with King Miraz. There is no way that boys are better than girls in the Narnia stories.

![]()

But – those Calormenes. ‘Narnia and the North’ is all very well, a stirring battle cry, but there’s no getting away from the fact that the brown-skinned people of the land called Calormen, south of Archenland, don’t come out of it very well. There are exceptions – the brave and proud Aravis from The Horse and His Boy, and the gentle and courteous Calormen knight Emeth in The Last Battle – but these remain exceptions. Calormen is depicted as a southern kingdom bordering a desert, ruled by fat, cruel, corrupt, dissolute, slave-owning aristocrats, and if you feel tempted to shrug and say ‘well, but it’s only a story’, imagine trying to explain to a Muslim child why the people of this land which so closely resembles that of The Arabian Nights worship a foul, cruel, stinking, four-armed, vulture-headed god called Tash? As a medievalist, Lewis must have been perfectly familiar with those prejudiced medieval romances which depicted Muslims as worshippers of an idol called Mahound – than which nothing can be further from the truth – and he should have known better than to take this propaganda and develop it into something even worse. The truth is, Lewis had little sympathy with or knowledge of Islam and he intensely disliked The Arabian Nights. It is seldom wise to write about something you hate. And so the charge of racial prejudice, I am afraid, does stick. Two strikes out of three.

Is it possible, then, to love the Narnia books in spite of all this? Of course it is. If we were only allowed to love what is perfect, there wouldn’t be very much left to love at all. If I no longer love them quite as much as I used to, if I now see faults where once I saw perfection, this is because I’ve grown up. Narnia is a child’s paradise: snowy woods, sunlit glades, talking animals, fauns who make you tea and buttered toast, bright waves, singing mermaids, and evil which can always be vanquished. A world in which there’s no school, no taxes, no economy: nothing boring at all. All of it presided over not by some adult ruler but by a gorgeous golden lion who comes and goes, but who is totally reliable and will always save the day.

Like Susan, I can no longer get back into Narnia, but I don’t see this as the tragedy my ten-year old self would have thought it. It’s because I’ve grown. And Narnia was part of my growing. It’s always there in my past, and it’s still there now, today, tomorrow, for any child who wants to open the wardrobe door and push past those fur coats…

“This must be a simply enormous wardrobe!” thought Lucy, going still further in…. Then she noticed there was something crunching under her feet. “I wonder is that more mothballs?” she thought, stooping down to feel it with her hand. But instead of feeling the hard, smooth wood of the bottom of the wardrobe, she felt something soft and powdery and extremely cold. “This is very queer,” she said, and went on a step or two.

Next moment she found that what was rubbing against her face and hands was no longer soft fur but something hard and rough and even prickly. And then she saw that there was a light ahead of her; not a few inches away where the back of the wardrobe ought to have been, but a long way off. Something cold and soft was falling on her. A moment later she found that she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air.